The Dressmaker Chase: The Ogle Gown Company

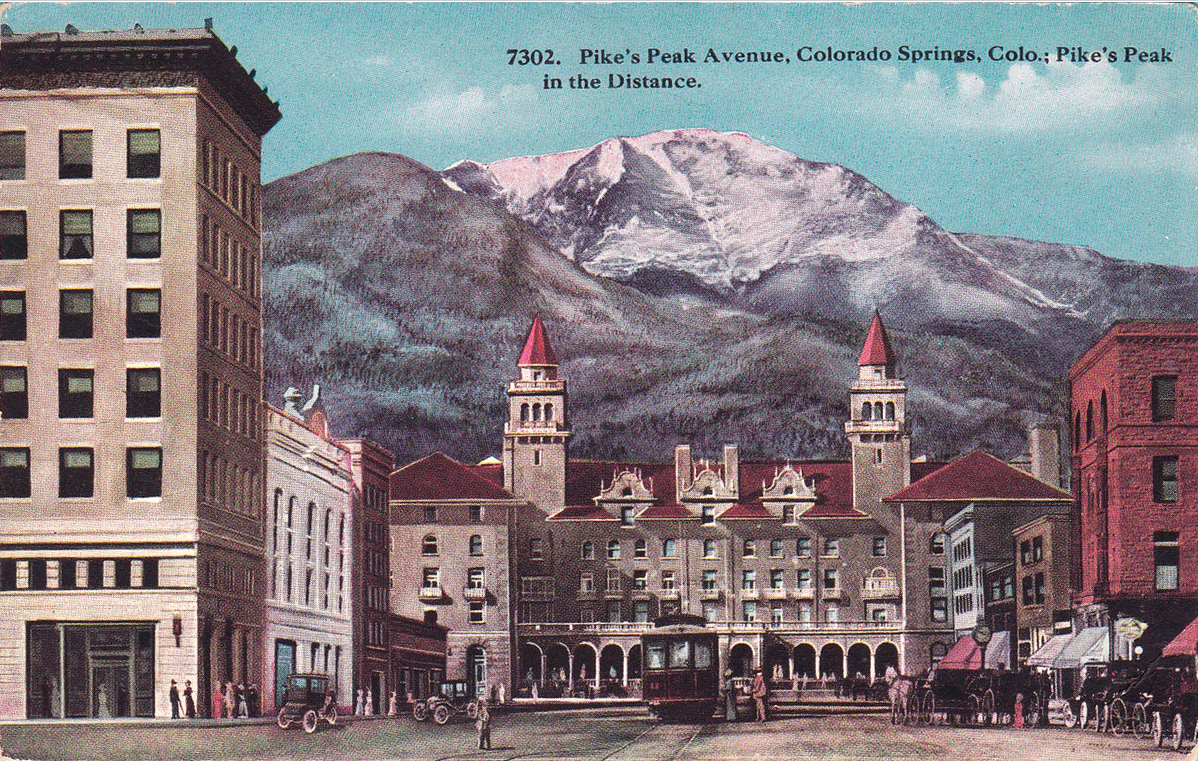

In the early years of the twentieth century, three women - Englishwoman Mary Jane (Hill) Fraser, Virginian Emmadean (Hanger) Ogle, and Connecticut-born teacher Julia M. Patten - were responsible for building the foundation of what was to become the Colorado Springs, Colorado-based Ogle Gown Company.

Mary, born in England around 1860 and the wife of Robert A. Fraser, moved to Colorado Springs with her husband around 1894. The couple likely came to the area for the same reason thousands of others did in the waning years of the nineteenth century - to seek the drier climate, high elevation, and fresh mountain air physicians of the day said Colorado offered sufferers of tuberculosis. Robert Fraser was one such sufferer.

The climate only put off the inevitable and when Robert died of tuberculosis in 1896, Mary almost certainly found herself in financial straits. She needed an income after her husband’s death. A dressmaker, she found employment at Giddings Brothers, a local department store. She was quickly placed in charge of their dressmaking department and worked there for six years before making the decision to establish a dressmaking company of her own from her home at 228 N. Tejon Street, called the Fraser Dressmaking Company. By 1903 she employed at least sixteen women.

We don’t know how Mary Fraser met Julia M. Patten, a Connecticut native born around 1860. Patten was an educated woman with an A.B. (the abbreviation of “artium baccalaureus,” the Latin name for the Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree) in Mathematics and History who in 1896 had been a faculty member of the Colorado Springs High School. Perhaps Patten had been a client of hers, as Patten’s job demanded she maintain an impeccable presentation.

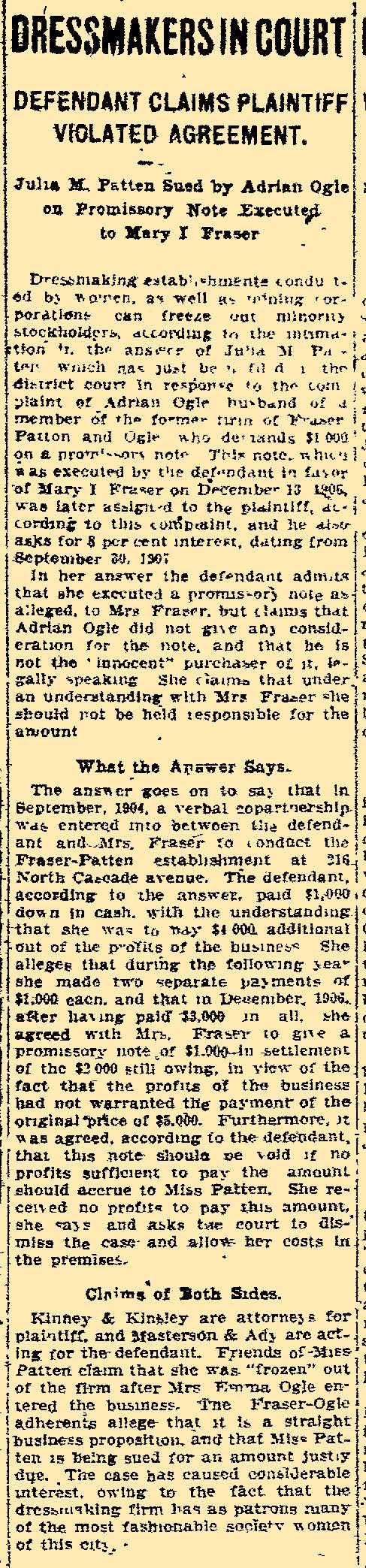

Colorado Spring Gazette, June 27, 1908

A 1910s Ogle Gown Ensemble, from the Fashion Conservatory Label Archive.

In any event, in September of 1904, Fraser and Patten entered into a verbal partnership to establish the Fraser-Patten Dressmaking Company out of Fraser’s new residence at 216 N. Cascade Avenue. In December of 1905 Patten made the partnership official and gave Fraser a promissory note to purchase a half interest in the business.

What role each woman played in the management of the business isn’t known but Fraser appears to have overseen the daily dressmaking work, as advertisements the company published for shirtwaist and skirt makers consistently asked potential employees to apply to Mrs. Fraser. By the end of 1905, Fraser-Patten Dressmaking Company employees numbered over twenty.

One of these employees was dressmaker Emma Ogle, who had worked for Mary Fraser during her time at Giddings Brothers. Ogle, born in Virginia around 1871, had by 1905 already had a spate of bad luck. In 1901 she had been badly burned in a gasoline explosion and in 1903 she and her husband Adrian, a conductor for the Colorado Springs Rapid Transit Company, had almost died of food poisoning after eating pineapple ice cream.

Ogle was liked and respected well enough by both Fraser and Patten to invite her to join their firm in the fall of 1906. Fraser and Patten went on a buying trip to Paris that July and returned in September. By late October, the three women filed their incorporation papers for the new Fraser, Patten and Ogle Dressmaking Company.

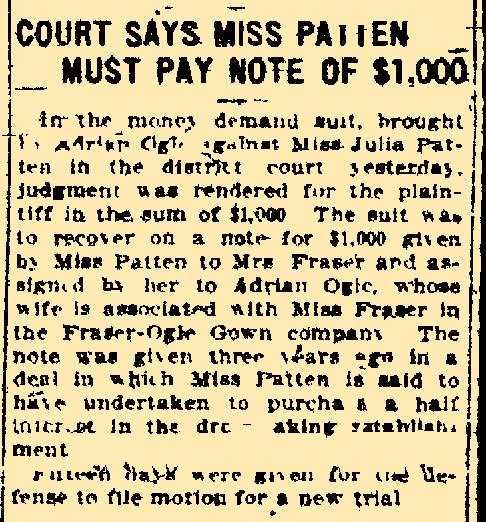

But - if you’ll pardon the pun - things were beginning to unravel by 1908. The Colorado Springs Gazette reported a suit brought by Adrian Ogle against Julia Patten regarding the promissory note Patten had given to Fraser in 1905. Ogle had bought out the note from Fraser in 1907 and assumed the debt, which meant Patten owed Ogle rather than Fraser for the outstanding funds. Patten, who had already paid two-thirds of the debt, said she’d made a verbal agreement with Fraser to settle the debt in full by paying fifty percent of the remaining balance because the company’s profits hadn’t warranted the original price. The case came before the district court in June 1908 and in March 1909 the court found Patten had to pay the remaining $1,000 she owed.

Colorado Springs Gazette, March 12, 1909

Many of the most fashionable society women in Colorado Springs were patrons, and not surprisingly, the suit drew much interest from the public. Not only did it illuminate early-twentieth century attitudes towards women in business with its references to “dressmaking establishments conducted by women,” it revealed hints of trouble with the profitability of the company and internal strife between the three partners in the firm. In her response to the suit, Patten said since Ogle had joined the company, she’d felt Fraser and Ogle intended to freeze her out. Perhaps they had. In late 1907, Patten had become involved in another dressmaking establishment, the Liberty Dressmaking Company, and this may have resulted in some hard feelings. Or perhaps Patten was being unjustly accusatory, and her debt to the business was the root cause of her issues within the company. Either way, by the early part of 1909 the damage was done and Patten was out.

The company - which in February 1909 restyled itself as the Fraser-Ogle Gown Company - moved locations once again, this time to the Plaza Hotel at 830 N. Tejon Street. The company only had half as many employees as it had the previous year, so the move was probably intended to capitalize on a captive audience; at the time, the Plaza’s three-story south hall, McGregor Hall, was a residence hall for female students of Colorado College. No doubt more than one resident of the hall visited Fraser-Ogle when they needed a new dress! Today, the Plaza Hotel is now the William L. Spencer Center at Colorado College.

The Plaza Hotel, Colorado Srings, CO. Circa 1910

Early 1911 saw more changes at the establishment. Mary Fraser decided to move to Pasadena, California, and sold out her share of the business to Emma Ogle. In January the company once again changed its name, this time to the Ogle Gown Company.

While Emma Ogle continued to run the company under the Ogle Gown Company moniker at least through 1915, city business directories and local newspapers show some changes in how the company and its employees were recorded. Advertisements by the company seeking employees disappeared from the Colorado Springs local newspapers by 1913. The company name itself disappeared from directory listings after the 1915-16 directory was published. And in 1916 through 1917, the ladies who in early directories had been in the employ of the Ogle Gown Company were either noted as seamstresses or as working for “Mrs. E. D. Ogle” instead of a designated company. It seems safe to assume at some point after the 1915-16 directory was published, the Ogle Gown Company was no longer in existence.

A 1910s Ogle Gown lable, from the Fashion Conservatory Label Archive.

The end of the company doesn’t finish the stories of the three women involved in its birth and evolution. By 1920 Mary Fraser was back in Colorado Springs working in her own shop as a dressmaker. Her death date is unknown. Emma Ogle’s husband Adrian died in 1922 and by 1930 Emma had remarried and moved to Los Angeles; after her second husband’s death in 1941 she moved back to Colorado Springs and died in 1954. And Julia M. Patten? Her whereabouts after 1910 are unknown.

by Patricia Browning

A native of the Midwest, Patricia got her archivist degree in Information Management and Preservation at the University of Glasgow. Her lifelong fascination with research saturates nearly every aspect of her life. These days when she’s not nose-deep in research on vintage fashions and their labels, Patricia can usually be found doing genealogy or working on her pet project on David Tennant’s early theatre career in Scotland.

An interesting aside...

In 1912, Emma Ogle’s cousin May Birkhead wrote to her about a tragedy she’d witnessed. Miss Birkhead was a passenger on the Carpathia, the ship who rescued and returned the survivors of the Titanic to New York City. One part of her letter to Mrs. Ogle reads as follows:

“A steward who was saved told me he went to one of the first cabin passengers, a woman, whom he told to dress and put on a life preserver. She merely laughed and said, ‘If that little bump is all that has happened, I’ll stay right here.’

“Madam,” replied the steward, “my orders from the captain are for you to dress and put on a life preserver.”

“She replied, “My orders for myself are to get back into bed and go to sleep again” And she did, paying for the act with her life.”

If you’re interested in another fashion story involving the Titanic - from the viewpoint of a survivor - then head over to Farquharson & Wheelock Suffer a Titanic Tragedy.

Do you know more?

If you have any further information about Mary Fraser, Emma Ogle or Julia M. Patten, we'd love to hear from you!

References:

“Dressmakers In Court: Defendant Claims Plaintiff Violated Agreement.” (27 June 1908). The Colorado Springs Gazette [Colorado Springs, CO], p.5. Retrieved 24 Jun 2021 via Newspaperarchive.com.

“Court Says Miss Patten Must Pay Note of $1,000.” (12 March 1909). Colorado Springs Gazette [Colorado Springs, CO], p. 5. Retrieved 24 Jun 2021 via Newspaperarchive.com.

“Wanted-Help.” (26 March 1905). Colorado Springs Gazette [Colorado Springs, CO], p. 11. Retrieved 24 Jun 2021 via Newspaperarchive.com

“Personal Mention.” (22 July 1906). Colorado Springs Gazette [Colorado Springs, CO], p. 8. Retrieved 24 Jun 2021 via Newspaperarchive.com.

“Incidents Rescue by Carpathia Told by a Colo. Springs Woman.” (28 April 1912.) Colorado Springs-Gazette [Colorado Springs, CO], p. 9. Retrieved 25 Jun 2021 via Newspapers.com.

Colorado Springs City Directories: 1879-1922. Pikes Peak Library District, 2019.

“Colorado State Incorporation Records.”Colorado State Archives, State of Colorado 2021.