Fashion & Social Impact: Apparel & Dissent

A participant in the Insurrection from Why Rioters Wear Costumes by Vanessa Friedman; January 7, 2021. Jason Andrew/The New York Times.

In Scarlett Newman’s Teen Vogue article ‘A Brief History of protest clothing,’ the author poses an interesting question: “What does an activist look like?” This question is related to something we’ve been talking about a lot at Fashion Conservatory recently; the ability of apparel (or costume) to communicate an opinion, a stance, or a political persuasion. Clothing that informs others about the wearer before words are ever spoken.

The Black Panthers march in New York in protest of the trial of co-founder Huey P. Newton in Oakland, California; July 22, 1968. Bettmann/Getty Contributor.

Given the state of the world at the moment, right now, right in the middle of 2022, these questions, these ideas, and hopefully the discussions they might start, seem more important than ever.

One big concept worth consideration is how our choices in clothing can show our support as we #StandWithUkraine, and whether choosing to do such a thing is a form of protest, or activism, or supportive. The choices we make can change the world, good or bad. Clothing is, or can be, a tool for change. Or a way to initiate or support a movement towards change.

The First Lady (from 2017-2021) wearing a jacket that reads “I really don’t care. Do U?” leaving for the Texas Migrant Boarder Crisis in late June 2018. Mandel Ngan/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

One quick point before we dive in here- there don’t always have to be definitive, objectively true answers to some of the questions I’m posing. If the goal is to start conversations, to confront our own biases, and to apply what we learn to making the world better (and kinder) then it’s important to try and think bigger than what we know, or assume we know, now. There aren’t necessarily going to be a lot of answers in this article, but this is a huge topic, and if we want to be nuanced in our discussion (we do), then this has to be a longer conversation. Otherwise we risk being overly general, or convoluted, and that’s not helpful.

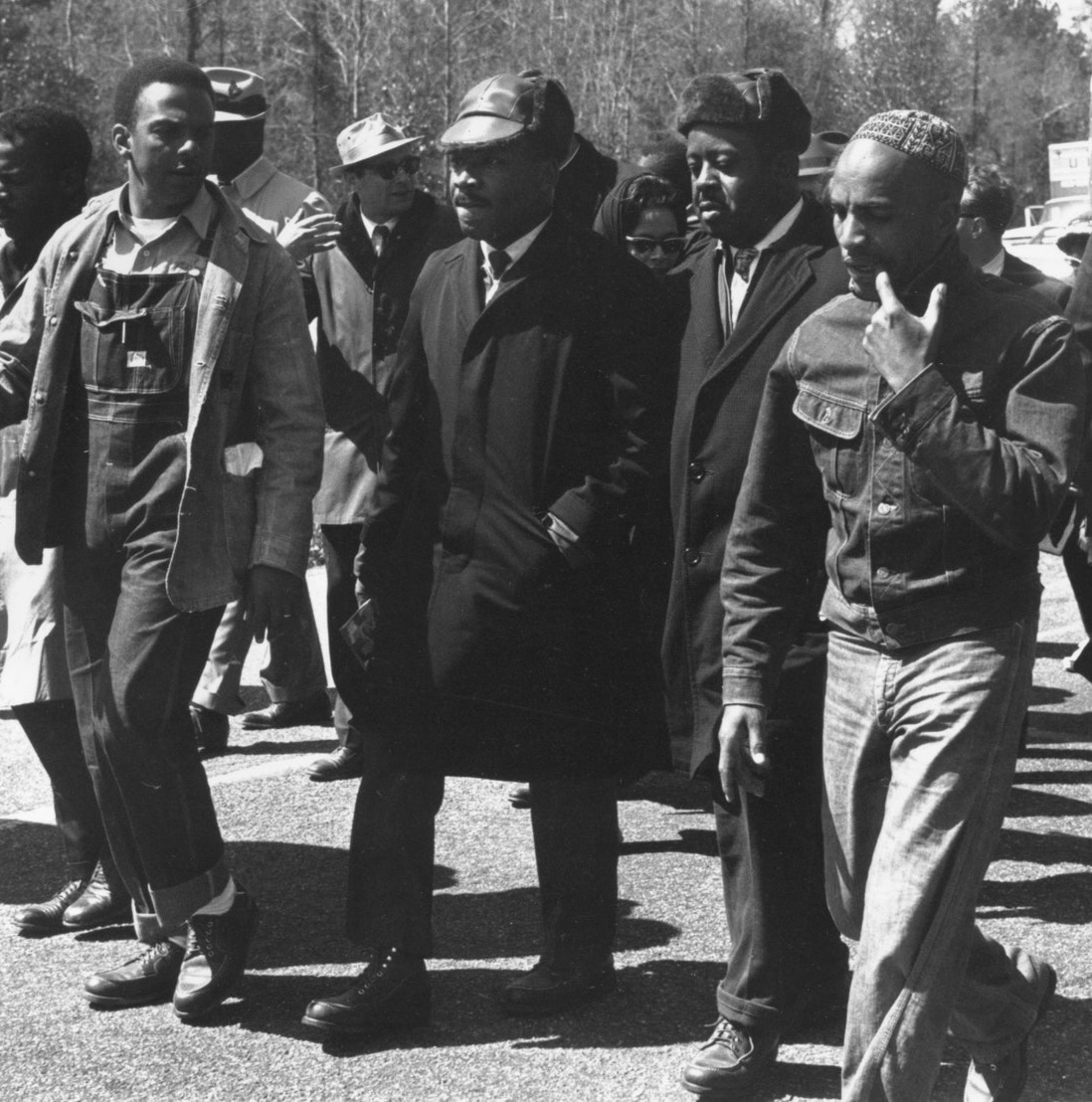

Dr. Martin Luther King leading a civil rights march in Alabama; March 1965. William Lovelace/Express/Getty Images.

So let’s ask questions, let's discuss the finer detailed points that matter in this context. Then we can go deeper, look at specific eras and events in history and better understand how and why apparel has been utilized as a means of social, political, or other kinds of protest, literally for centuries. I could start with a point about how the collective image of Rosa Parks sitting at the front of that bus is indelibly linked to her hat, coat, and checked dress. Or Dr. Martin Luther King in his carefully somber suits.

But let’s start with this century, this decade, as perhaps that will make this topic more relevant to the world we live in, and not delegate this discussion to events in history. There are two polarizing examples from 2021, which seem like a good place to start. The intent is to pick this conversation up later, to let you all gestate on the ideas I’m posing here today. I’d love feedback, or questions, or to hear points you may have to make about all of this. Because a conversation about change cannot be one sided; and nothing effective can happen without some sort of discourse, even if you agree with my perspective.

Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and fashion designer Aurora James at the Met Gala in 2021. Mike Coppola/Getty Images.

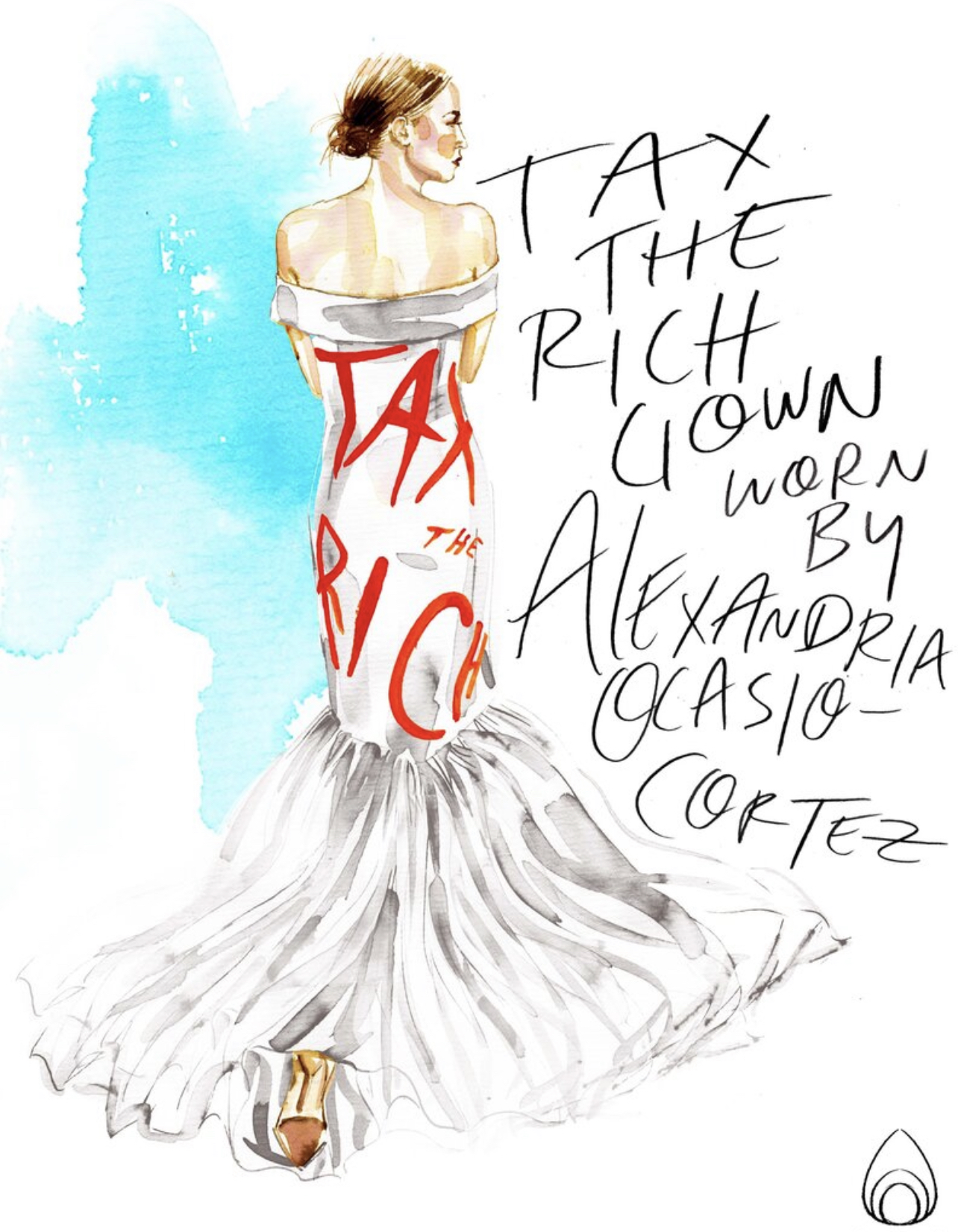

When Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez attended the Met Gala in 2021, she wore custom Brother Vellies (designed by the brand’s founder Aurora James), an “ivory wool jacket dress with an organza flounce and the message ‘Tax the Rich’ emblazoned in red across her back.”

The internet broke, to use the parlance of our very strange times, as soon as photos of AOC in the dress made it online. Shortly after, a thousand think-pieces (or just nasty comments disguised as journalism) appeared in the hours and days that followed. Was choosing that look and wearing it to THAT party a protest? Judith Thurman, writing for The New Yorker said that the “dress wasn’t hypocritical, as some have claimed, but it wasn’t radical, either.” Which raises all kinds of questions worth asking.

Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in gown designed by Aurora James for the 2021 Met Gala.Credit. Samantha Hahn for Brother Vellies.

When does apparel become a form of protest? Does clothing with messages of support for specific causes count as protest? Is there space in our cultural lexicon for a spectrum to exist, from supportive to protest or activism? (And will the use of the word ‘spectrum’ prevent some people from considering such an idea? Does that matter?) And then what about activism, when is activism the same thing as protest, when is it totally different, and when/why do those distinctions matter?

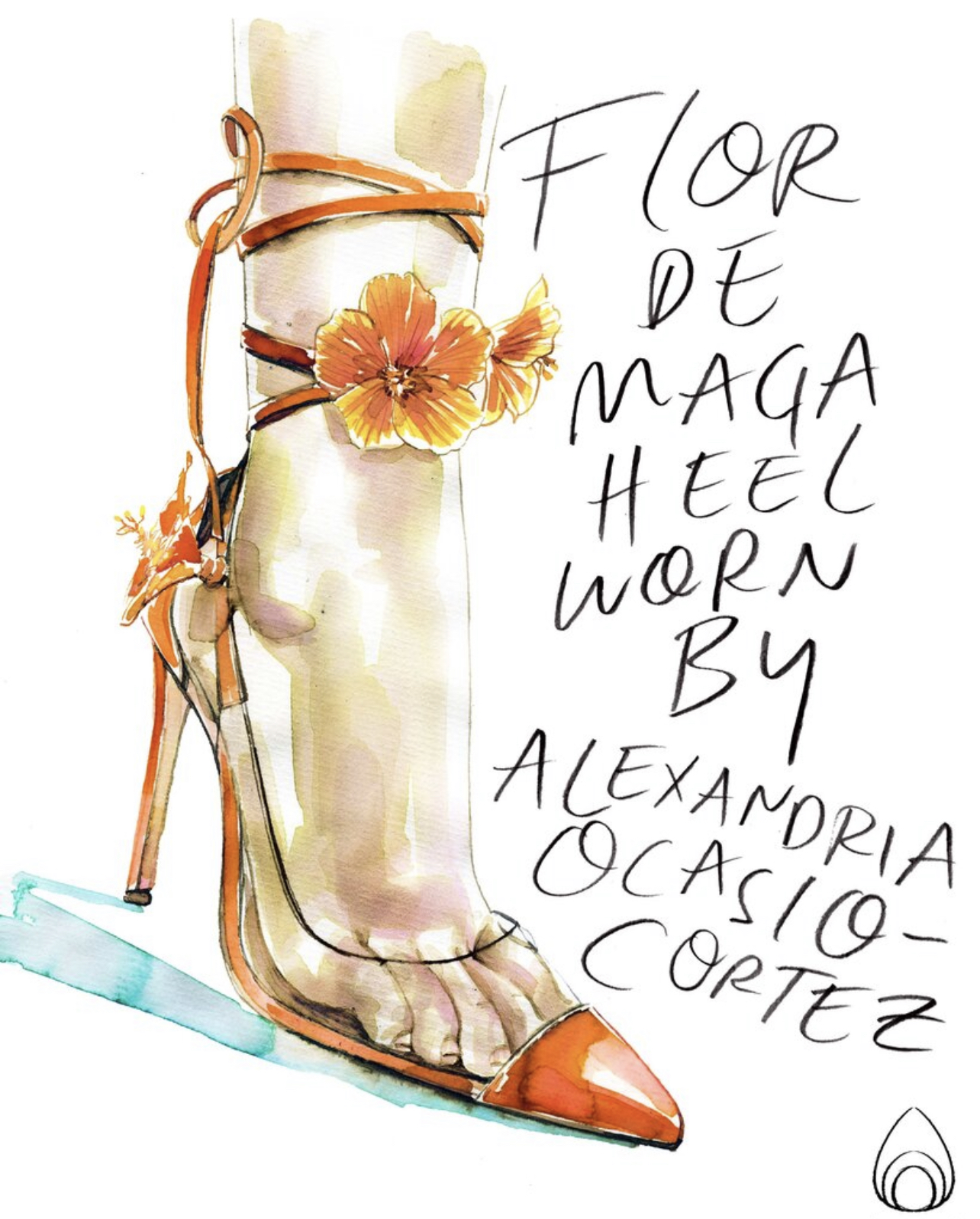

Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's Shoes for the 2021 Met Gala.Credit. Samantha Hahn for Brother Vellies.

Eric Munchel, in the Senate chamber on January 6, 2021. Win McNamee/Getty Images

When absolute madness broke out on January 6, 2021 in Washington, DC, which is being dissected right now in the congressional hearings regarding the events of that day, there were many examples of different forms of carefully curated costume. It was purposeful dressing, the clothing worn by those who descended upon the capital of the United States was designed specifically to identify the like-minded, to intimidate those who objected to the siege, and for some reason, to assign a (terrible) cis-gendered-white-person version of Shamanism to the whole affair, as though that added some kind of spiritual significance to treason. Vanessa Friedman said "they came dressed for chaos."

Jacob Chansley during the Capitol riot in Washington. AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta.

But it cannot be said that the para-uniforms, the coordinating outfits, the costumes worn, that any of it was done unintentionally. There is an obvious kind of intention that goes into having matching, sometimes logo-bearing shirts made prior to an invasion. Thinking about that intent, what it means looking back at events past, what is proven by the preparations made in advance… There are many instances in criminal proceedings, or even civil matters, when the apparel choices made by one party or another affects the way a jury turns.

From Vox News reporter Tess Owen's Tweet (@misstessowen) on January 6 that reads: I asked these guys if civil war was what they wanted. “Yes” they replied.

As Americans wait for their congressional body to make a decision about the events of that dark day in January, 2021, we are also waiting to hear what they believe counts as premeditation, what counts as an organized group. What is covered by the First Amendment’s Freedom of Assembly, and what takes that too far.

What proves that a group is intentionally together, and acting in concert, as though with one voice, more than the purposeful choice of dressing your regional group’s contribution in matching shirts? And what will Congress’s decision mean for the future of the Right to Assemble? Only time will tell.

Since 2018 fashion historian Rachel Elspeth Gross has run her popular blog, Today’s Inspiration, about the history of high-end fashion design. Drawing more than 40,000 individual readers every day; Rachel’s ever-growing audience includes some of the biggest names in Fashion, Haute Couture, Fashion Journalism, and Fashion History academics. Her work has been featured in Women’s Wear Daily, the New York Times, Italian Harper’s Bazaar, and The National News; writes for The Vintage Woman magazine.

A formally trained designer in her own right, in her spare time Rachel recreates 19th century ball gowns from scratch.

Sources:

Rogers, Katie (June 21, 2018) Melania Trump Wore a Jacket Saying ‘I Really Don’t Care’ on Her Way to Texas Shelters. The New York Times. Accessed June 15, 2022.

Burns, Bridget, Liao, Marina, and DuFour, Bridget (October 24, 2019) The 65 Most Controversial Celebrity Outfits of All Time. Elle Decor. Accessed June 15, 2022.

Farra, Emily (April 23, 2020) Fashion Creates Culture, and Culture Creates Action: Céline Semaan on the Industry’s Role in Times of Crisis. Vogue. Accessed June 15, 2022.

Newman, Scarlett (November 27, 2020) A Brief History of Protest Fashion; How organizers have used fashion to give visual currency to different sociopolitical movements. Teen Vogue. Accessed June 15, 2022.

Friedman, Vanessa (January 7, 2021) Why Rioters Wear Costumes: As star-spangled superheroes and militiamen, the rioters of D.C. dressed with a license for mayhem. The New York Times. Accessed June 15, 2022.

Heorge-Parkin, Hillary (January 12, 2021) Insurrection merch shows just how mainstream extremism has become: As rioters stormed the Capitol, their shirts spoke loud and clear. Vox News. Accessed June 15, 2022.

Karni, Annie (September 15, 2021) A.O.C.’s Met Gala Dress Triggered Strong Reactions. The New York Times. Accessed June 15, 2022.

Thurman, Judith (September 17, 2021) What Counts as Protest Fashion; Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Met Gala dress wasn’t hypocritical, as some have claimed, but it wasn’t radical, either. The New Yorker. Accessed June 15, 2022.

Pinnock, Olivia (May 3, 2022)Fashion and Protest: How Blue and Yellow might become the new black. EuroNews: Culture. Accessed June 15, 2022.

Testa, Jessica (September 16, 2021)A.O.C.’s Met Gala Designer Explains Her ‘Tax the Rich’ Dress. The New York Times. Accessed June 15, 2022.

The Constitution Annotated; Analysis and Interpretation of the U.S. Constitution.Amendment 1.4.1: Freedom of Assembly and Petition. U.S. Congress. Accessed June 15, 2022.