No, You're Not Crazy; Apparel Sizing Makes Zero Sense

It’s important to remember that prêt-à-porter, the French term for ready to wear (off the rack, or RTW) clothing became not just prevalent, but possible very recently. Etymologically speaking, prêt-à-porter wasn’t a word in common use

until 1959.

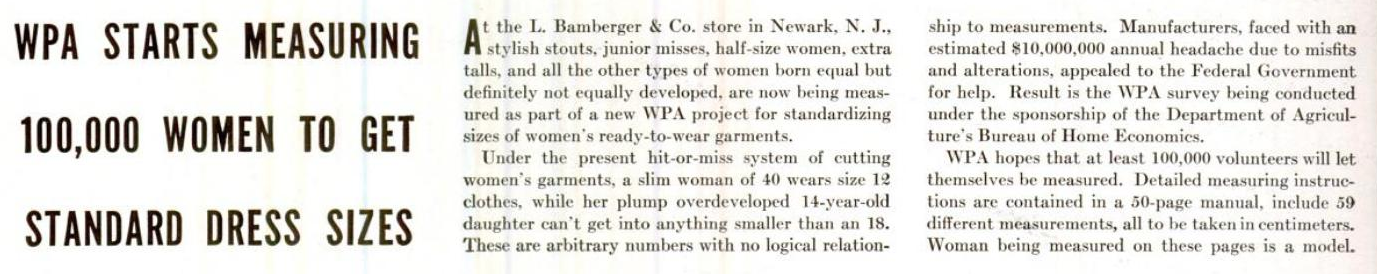

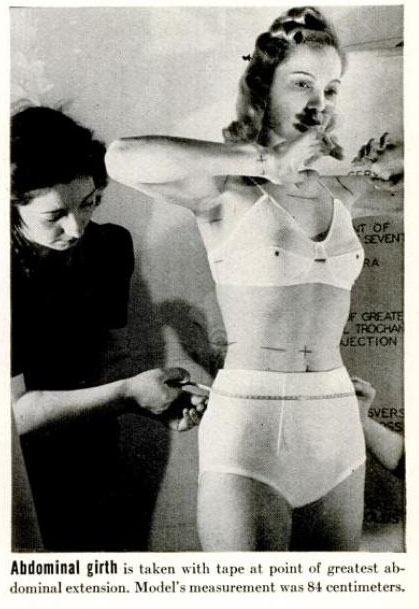

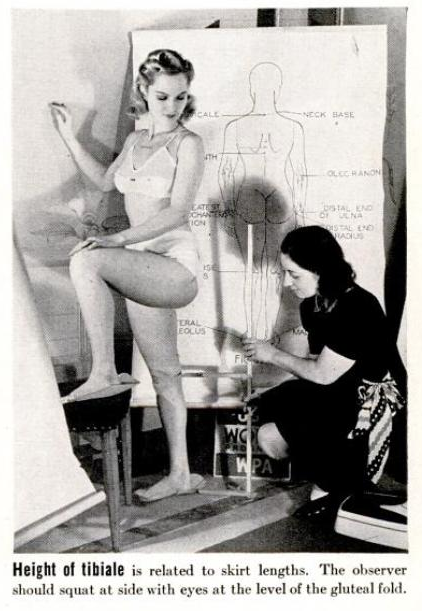

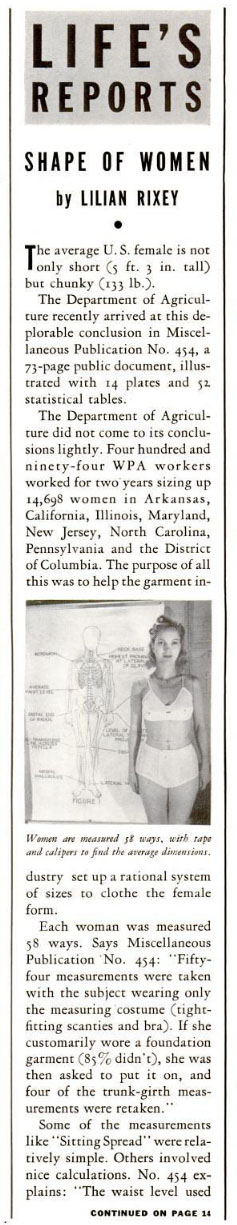

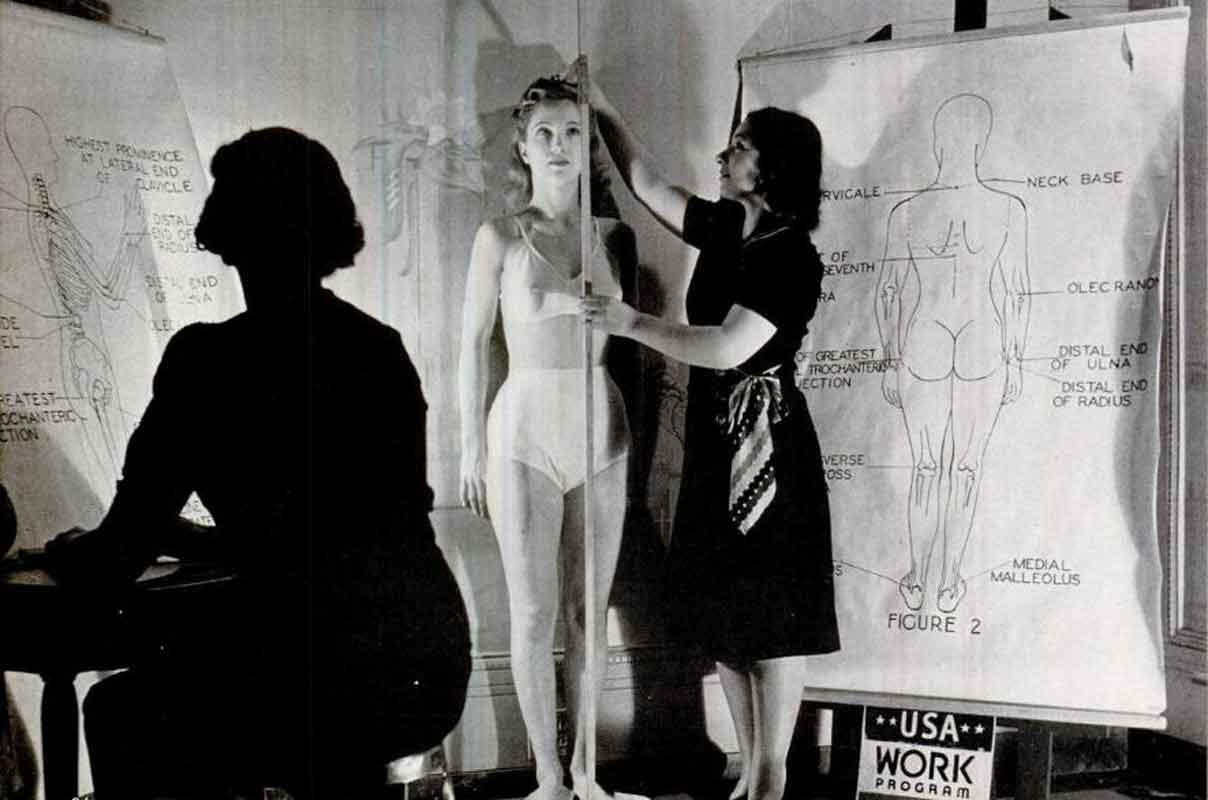

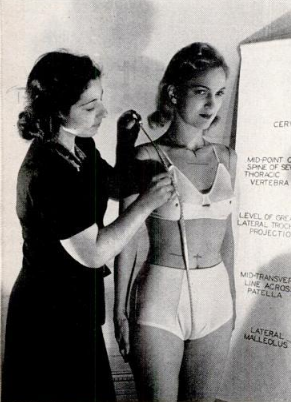

Of course there were problems with the data collection. Women of color were measured, but not included in the final tally of numbers. There was also a cash incentive, the study was paid, which further reduced the diversity of the women who elected to participate, and meant that the information collected included a disproportionate number of women suffering from malnutrition. The best system that O’Brien and Shelton were able to develop was based on a combination of height and weight, about 27 different sizes, but there were simply too many variables between women’s body types to create a fit system that was simple and consistent. (Luckily, they decided to trash the idea someone had about basing the measurement system on total body weight.) All the issues with the data collected during the study did not stop the [then] National Bureau of Standards (NBS, today the National Institute of Standards and Technology), from making this type of sizing its Commercial Standard for the American fashion industry. Mail order companies quickly adapted to the government standard sizing. There were some positive impacts, some consistency, imperfect as the sizing system was for almost all women.

In 1958 a system was created, sizes ranging from 8-72, which is still well known today. This system was still based mostly on bust size, but included letters to indicate whether a garment was long, full, or slender. By 1970 it had proven to be so unpopular that once again it was refined. That same year, the NBS downgraded their language about sizing, reclassifying standard sizing as a Voluntary Product Standard. In 1983 the concept of government standard sizing was completely withdrawn in the US. Since then, it has been chaos. Vanity sizing took off almost immediately after the American Federal government dropped its interest in standardized sizing, complicating everything further.

Here at Fashion Conservatory, a lot of work has gone into finding solutions to issues like this one, applying common sense and systems to make finding, buying, and selling vintage a better experience for everyone. Make sure you’ve signed up for the mailing list, we’ve got a lot of stories, solutions, and expanded resources coming soon!

Further Reading:

For more information about the WRA Survey, check out

this January 15, 1940 issue of Life Magazine.

The full article starts on page 24

References:

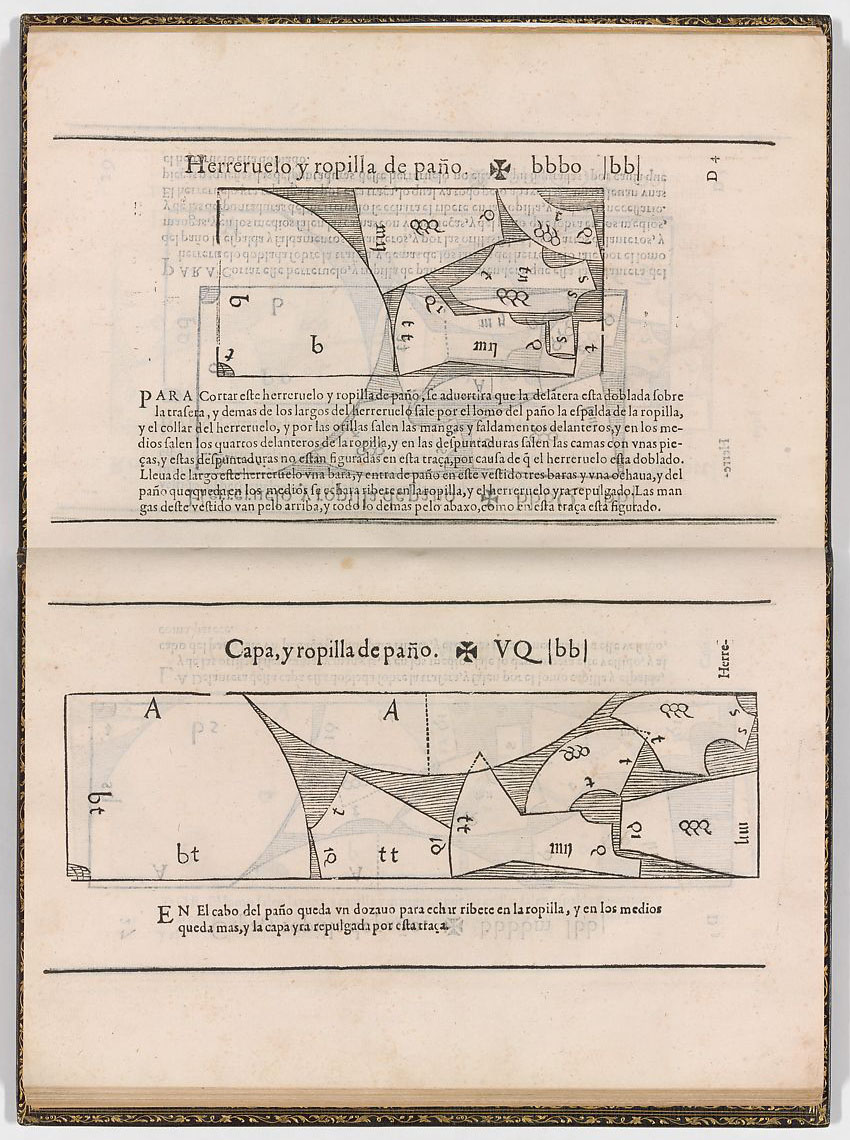

de Alcega, Juan. “Libro de Geometría, Práctica y Traça.” Madrid: Guillermo Drouy, 1589. Accessed through the Metropolitan Museum's Website.

Hecklinger, Charles. “Hecklinger's Ladies' Garments.” Catalog, Publisher unknown, 1886. Collection of Library of Congress; Americana. Housed at the Internet Archive/Wayback Machine.

U.S. Department of Commerce. Body Measurements for the Sizing Of Apparel. June, 2006. Housed at the Internet Archive/Wayback Machine.

Schrobsdorff, Susanna.Fashion Designers Intro duce Less-than-Zero Sizes. Newsweek Magazine, October 17, 2006.

Clifford, Stephanie. “One Size Fits Nobody: Seeking a Steady 4 or a 10.” (24 April, 2011). The New York Times [New York City, New York].

Ingraham, Christopher. “The absurdity of women’s clothing sizes, in one chart.” (11 August, 2015). The Washington Post [Washington, D.C.]

"A Short History of U.S. White Women’s Measurements Used for Pattern Making; or… Why Nothing Seems to Fit.” AnalogMe, Typepad. November 30, 2011.