Virginia Oldoini, Countess of Castiglione, Part I

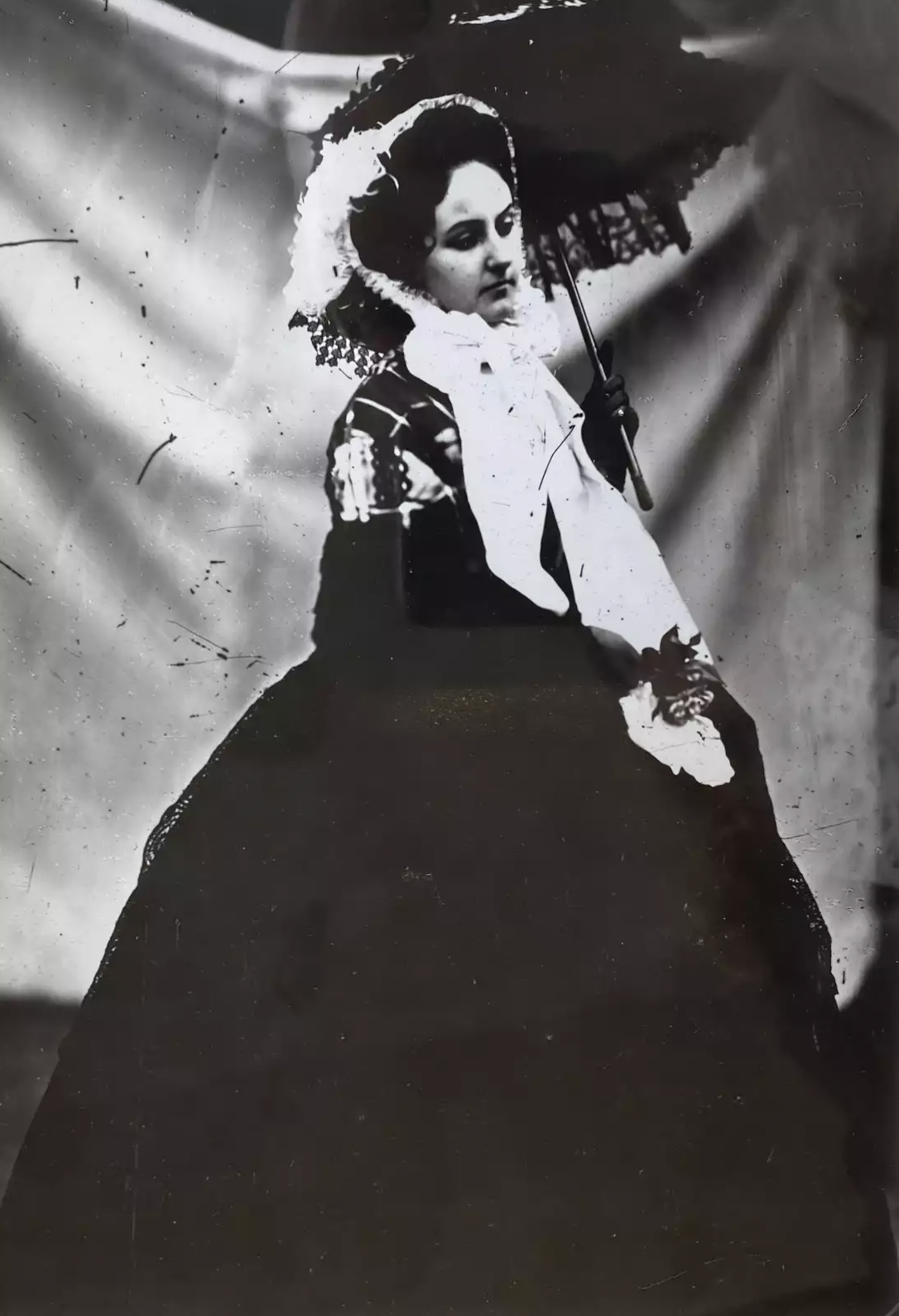

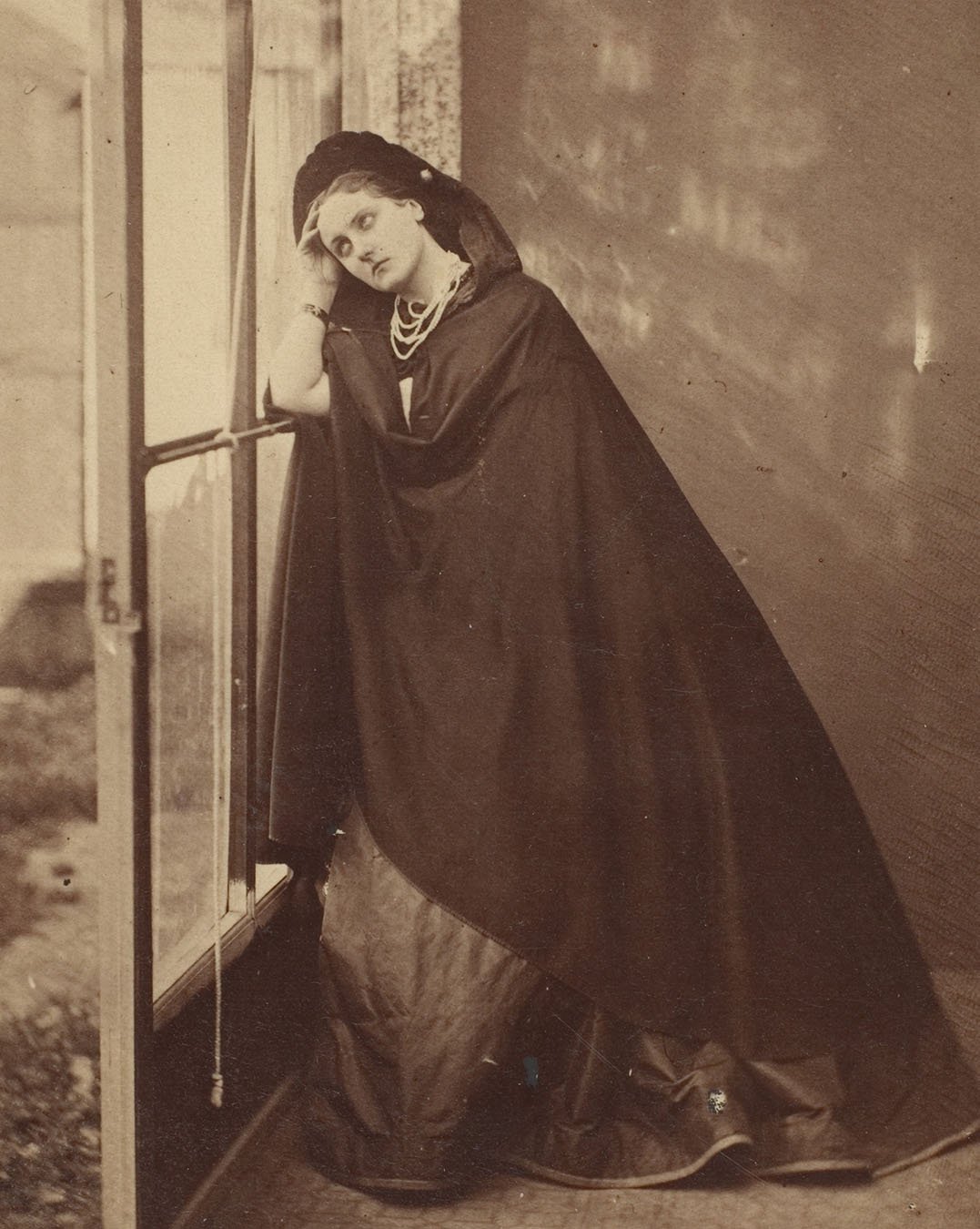

A variation on the "Ritrosetta" dress; 1864. Albumen silver print.

Virginia Elisabetta Luisa Carlotta Antonietta Teresa Maria Oldoini, Countess of Castiglione, was celebrated during her lifetime as the most beautiful woman in the world. Her lovers were some of the most powerful men in 19th century Europe. She was photographed around 700 times between 1856 and 1899, marking her as either the first or second most photographed person of the 19th century (an accomplishment perhaps only eclipsed by England’s Queen Victoria.) Yet she has now been mostly forgotten, or reduced to listicles which label her a narcissist. She meticulously documented her entire life; so much so that upon her death in 1899, the Italian government delayed the release of her estate to her heirs and dispatched a team to review her personal documents to ensure nothing embarrassing or problematic could be released. Afterwards, in a decision which erased her almost entirely from history, the majority of her personal papers and other untold treasures were destroyed. And why? Because in reality Castiglione was something between a spy and an emissary, and her careful machinations changed the very geography of her native Italy.

Portrait in a Black Dress (1856) by Pierre-Louis Pierson. Salted paper print with ink retouching.

Due in part to the extensive and careful photographic recordings Castiglione made of her exploits, however, some of her story has survived. She was certainly never the passive subject of a portrait. She collaborated with Pierre-Louis Pierson, a partner in the famed Mayer & Pierson photography studio. The studio was originally opened in 1855 by brothers Louis Frédéric and Léopold Ernest Mayer, and just before Pierson joined the studio in 1854, the business was described as a “palace of photography.” They soon became "Photographers of His Majesty the Emperor [Napoleon III]". By the time Pierson met Castiglione, Mayer & Pierson was arguably the most prestigious studio of the Second Empire period of French History.

Countess Castiglione and her son Giorgio de Castiglione, exact date unknown, probably 1860. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, albumen silver print from glass negative.

Photographs of the Countess of Castiglione were all taken very early in the history of photography; they were mostly albumen silver prints made from glass negatives, one of the first commercially exploitable techniques for printing photographic images onto paper. Castiglione was a hands-on participant in the photographic process and there are many indications she was the real artist, or art director, behind the work she produced with Pierson. Though she never wielded the camera herself, she directed the shoots, wrote out scenarios which she wanted to enact, and selected and styled the costumes, props, and furnishings. We know this because Castiglione was an obsessive record keeper, essentially a scrap-booker, and perhaps a bit of a hoarder. Negatives and test prints exist with her careful handwriting on the edges; instructions on how a shot should be trimmed, or what colors should be added when enhanced with paint. The Countess made sketches of future photos and kept notes on how to re-do a pose to better capture her vision at the next photoshoot. She kept a detailed diary of her plans (only fragments of which survived or are accessible) but the surviving information is decisive. To the Countess, Pierson was a necessary asset. Castiglione was lucky to have him, but he was also lucky to have her; a model before photographic modeling was a hobby or career. Together, they either created or forever changed narrative photographic portraiture

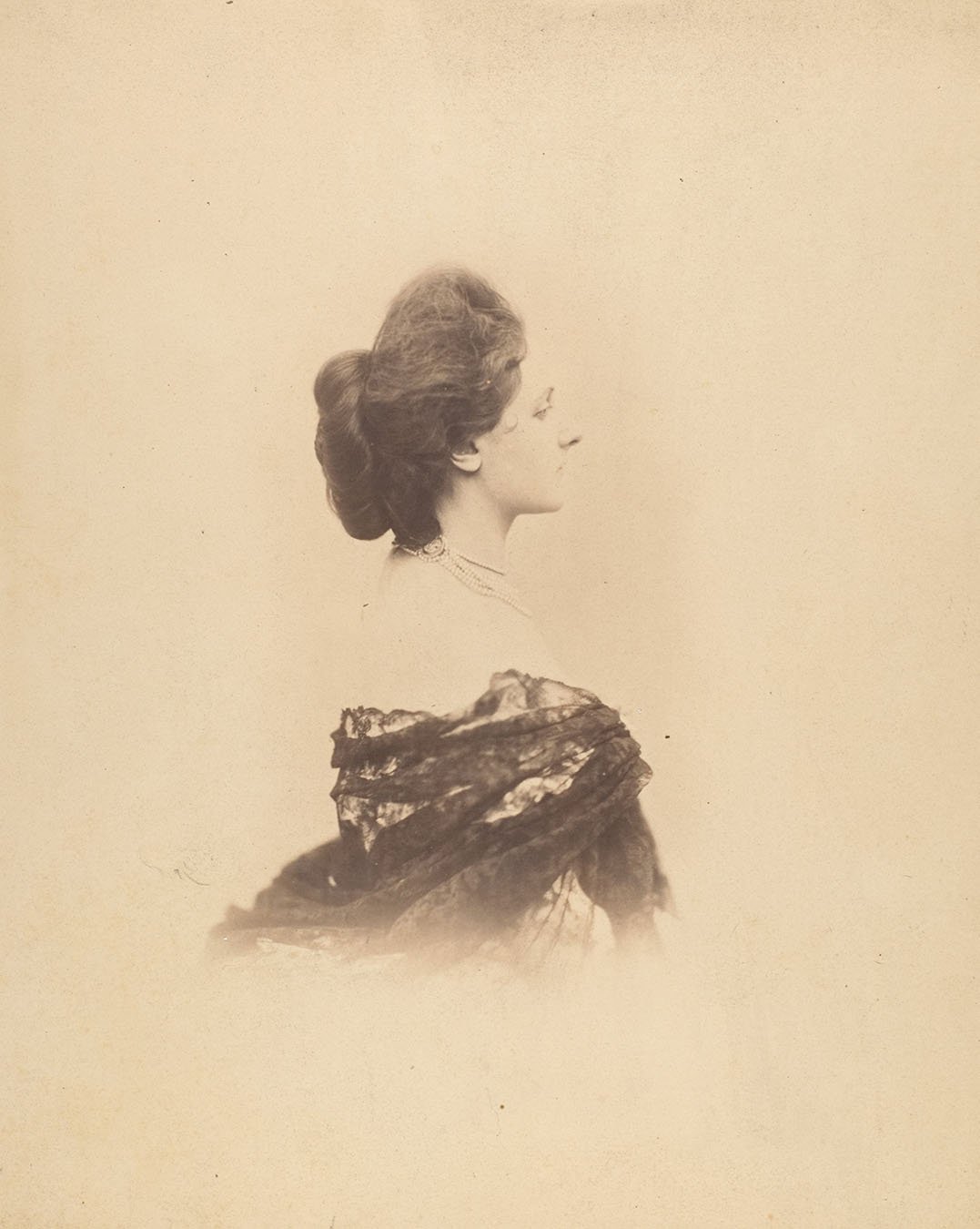

Profile with Chignon, 1859. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, albumen silver print from glass negative.

It’s important to understand how incredibly expensive photographic prints were in the mid-19th century. Photography was science as well as a new medium. It required specific training to use a camera, and the development process required dangerous and expensive chemicals. The concept of an intersection between science and fine art was new, and its mystique contributed to the price early photographers could demand. A plain daguerreotype without decorative painting could easily cost $5 or more in 1850. Adjusted for inflation, it would be like spending $150 or more for a single print of a black and white image, a prohibitive cost even for those with disposable income. The Countess, however, was never concerned with trifles like costs. If anything, she dealt exclusively in excess. She spent staggering amounts of money, mostly on clothes, but also on jewels, property, and entertainment. If not for Castiglione’s financial status and innumerable social connections, her portfolio of photographic work would have never been possible.

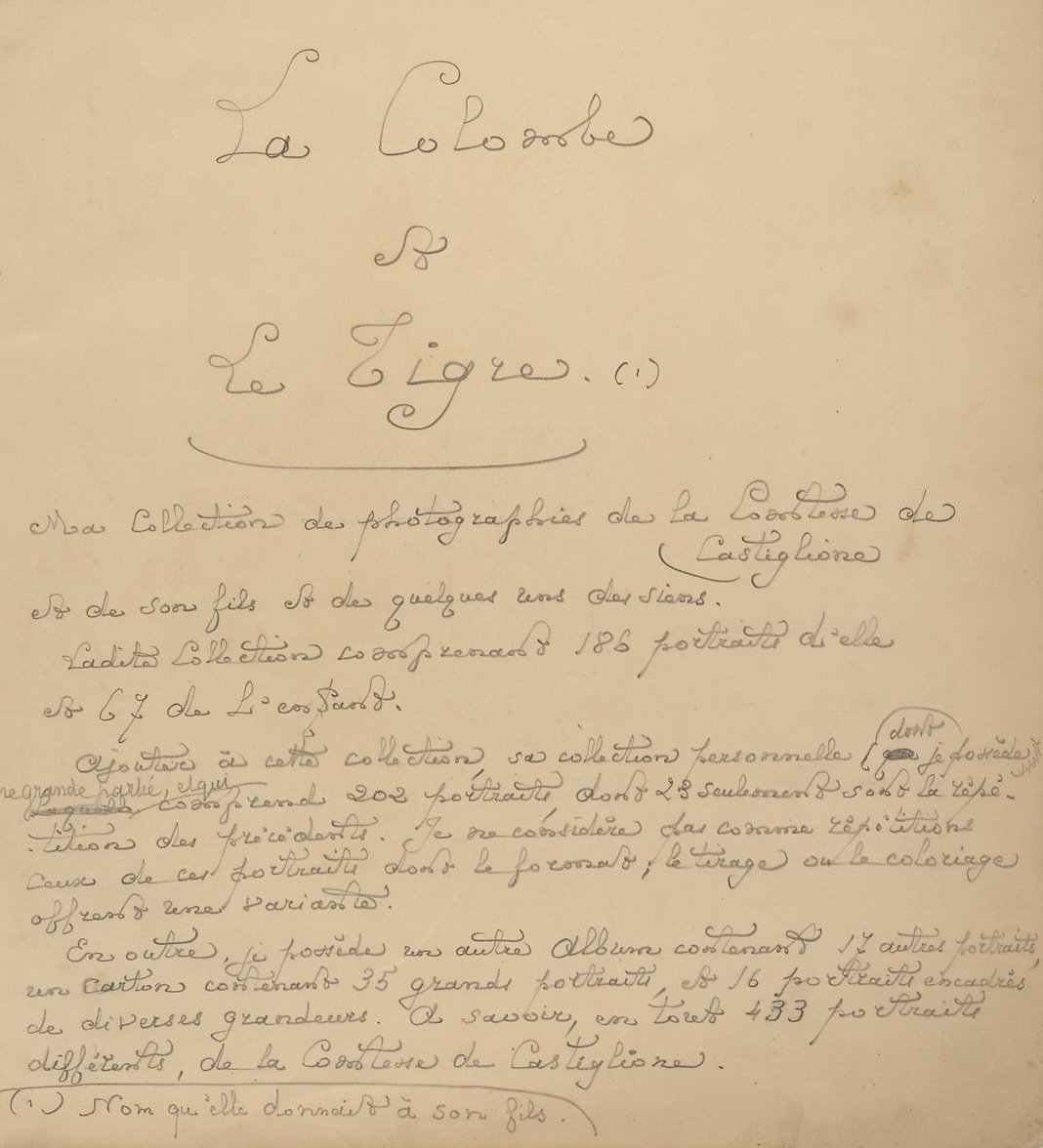

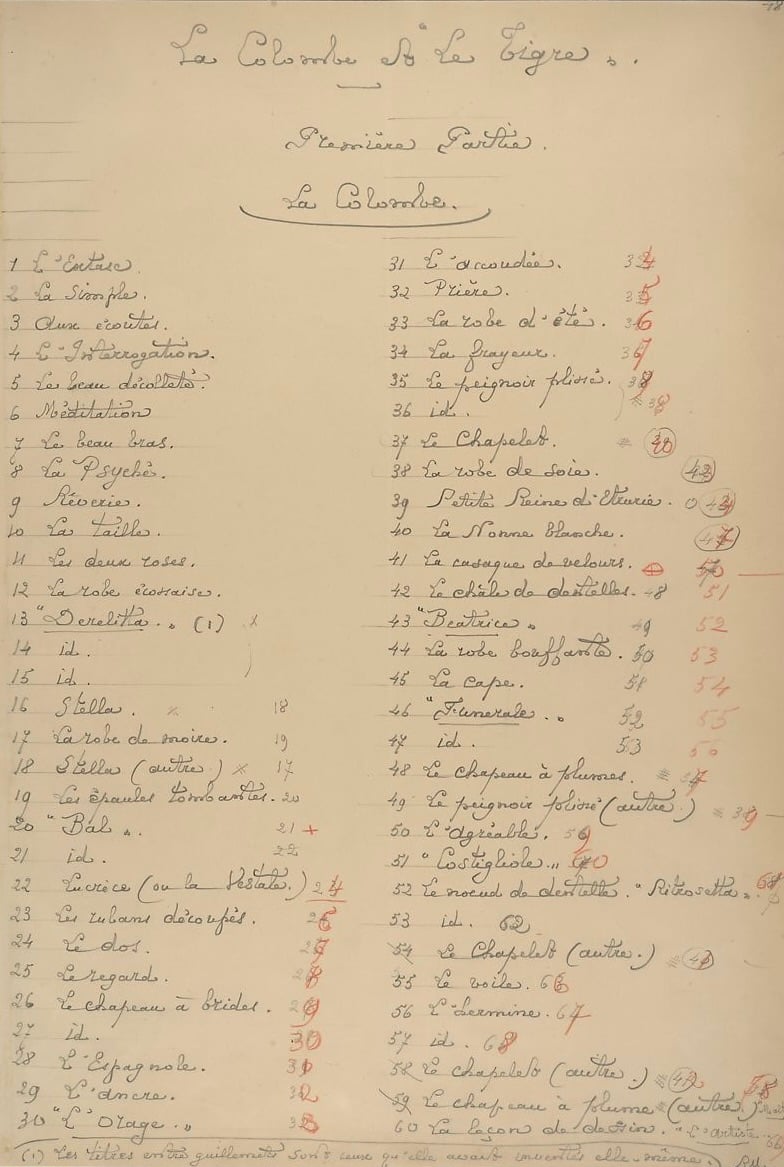

La Colombe et Le Tigre. Ma collection de photographies de la Comtesse de Castiglione, 1860s. Albumen silver print.

The Divine Countess was born into a family descended from an ancient clan of Florentine nobles. She was born on March 22, 1837 in La Spezia, a port city on the western coast of what is now Italy, and was then part of the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia. Her parents were Marquis Filippo Oldoini and Isabella Lamporecchi. Stories about her charm and beauty can be traced back to the earliest days of her childhood. By all surviving accounts the Countess was doted on, coddled, and generally spoiled in her youth. One of her only biographers, Frédéric Loilee, a French historian and contemporary, describes her childhood home as a “...perfectly authentic palace.” She liked to tell others her formative years were spent in a quaint, pastoral setting. Perhaps she thought it made her a more relatable, sympathetic figure.

La Colombe et Le Tigre. Ma collection de photographies de la Comtesse de Castiglione, 1860s. Albumen silver print.La Colombe et Le Tigre. Ma collection de photographies de la Comtesse de Castiglione, 1860s. Albumen silver print.

On January 9, 1854, at the age of 17, Virginia married Francesco Verasis, Count of Castiglione. Verasis was about a decade her senior, the marriage was arranged, and (at least on the Countesses’ side) loveless. Perhaps she was tired of the marriage proposals she had been fending off since she was twelve. Before the couple wed, Virginia informed Verasis she was indifferent to his presence and if they married, he could only blame himself for his future misery. But the Count was infatuated with his young wife, drunk on her beauty, and was willing to agree to anything she asked. She did what was expected and gave birth to a son, the only child the marriage would produce. Her duty performed, she effectively checked out of the marriage.

In December of 1855, Virginia and Verasis traveled to Paris, ostensibly to visit family, the Count (a son of Napoleon I and a minister of foreign affairs for Napoleon III) and Countess Walewski. The real reason was intrigue, possible spying, and schemes that changed the geography of Western Europe.

The White Nun, 1856–57. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, albumen silver print from glass negative.

In the mid-19th century Italy did not exist as it does in the modern sense; it was made up of small, fairly independent kingdoms, similar to city-states, which were largely under the thumb of Austrian rule. A secret group of revolutionaries calling themselves the Carbonari was able to ride the wave of political and social change that followed the French Revolution to instigate a nationalist movement. The process of organizing all of these individual states into a single kingdom had begun in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna. After decades of assassinations, wars, and families divided, a solid foundation was built from the states which saw the benefits of aligning their interests. But a single unified independent Italian kingdom could not truly be successful without the support of Emperor Napoleon III.

Giorgio de Castiglione, 1861, printed 1895–1910, by Pierre-Louis Pierson. Gelatin silver print from glass negative.

One of the principal actors in the plan to unify the peninsula was a cousin of the Countess of Castiglione. His name was Camillo Paolo Filippo Giulio Benso, Count of Cavour and Prime Minister to Emmanuel II, the King of Piedmont-Sardinia. Cavour was a scholar, an efficient bureaucrat, and an even more efficient schemer. He recognized Virginia was highly intelligent as well as beautiful and had a self-possession beyond her years, qualities which would attract the attention of powerful men. So he sent his stunning, ebullient young kinswoman to Paris with two goals in mind; catch the wandering eye of the skirt-chasing Napoleon III, and convince the Emperor to back the advancement of Risorgimento, the term referring to Italian unification, by “any means necessary.”

This story of Castiglione using her feminine wiles to convince a monarch to use his global influence to back her family's cause is an unrelenting rumor found in innumerable listicles and texts, online and off. But it is incomplete. It obfuscates the truth, easily found in surviving documentation. If it was a simple seduction story, it is likely the Parisian parlors of the late 19th century would have gossiped about an entirely different version of events. But the stars were aligned just so, and it turned out the countess already had a personal relationship with Napoleon III. For possibly unknowable reasons, this part of the story is mostly unexplored, except by Frédéric Loliée, and perhaps one or two others.

Béatrix, 1856–57. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, albumen silver print from glass negative.

Marquis Filippo Oldoini, Virginia’s father, had served as a Guardian to the son of Queen Hortense, making Louis Napoleon a regular visitor at Virginia’s family home. Even in childhood, Castiglione was charming and the two became friends. She was a child and he was a young adult, and there were comments only about the gentle and seemingly paternal affection that the otherwise aloof future-emperor would display. Castiglione had come to the Napoleonic courts for her society debut, so when she returned to Paris in 1855, the Countess was greeting a childhood friend. The emperor was possibly remembering some of the loving and simple life experiences of his youth, which were so unusual in his current station. Castiglione and her beauty had only been a rumor in the City of Light, until she arrived and removed any questions about her looks.

Béatrix, 1856–57, printed 1861–67. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, salted paper print from glass negative with applied color, painter unknown

Marquis Filippo Oldoini, Virginia’s father, had served as a Guardian to the son of Queen Hortense, making Louis Napoleon a regular visitor at Virginia’s family home. Even in childhood, Castiglione was charming and the two became friends. She was a child and he was a young adult, and there were comments only about the gentle and seemingly paternal affection that the otherwise aloof future-emperor would display. Castiglione had come to the Napoleonic courts for her society debut, so when she returned to Paris in 1855, the Countess was greeting a childhood friend. The emperor was possibly remembering some of the loving and simple life experiences of his youth, which were so unusual in his current station. Castiglione and her beauty had been a rumor in the City of Light until she arrived and removed any questions about her looks.

It is clear the Countess saw herself as a political influencer and a force to be reckoned with. She was also too ambitious to allow herself to be defined only within the role of wife. It’s not clear how much work it required to convince the Emperor to back her cause, but it is a fact that when Napoleon III and Castiglione reformed their friendship in his Parisian court, he was undecided about the concept of Italian statehood. The Emperor was haunted by what had happened to his namesakes and wanted to reestablish the monarchy, which he saw as his heritage. One way to guarantee it was to take Italy from the Hapsburgs and restore its independence.

It is entirely possible the Countess simply had good timing. The Congress of Paris had ended the Crimean War in 1856. When Castiglione arrived, Napoleon was still riding the accolades he’d received from his role as peacemaker during the war. The Countess was more than literate; she was exceptionally educated for anyone in her era, male or female. She could speak, read, and write in at least six languages and was able to converse with the Emperor as an intellectual equal. There is no doubt this enticed him. When Victor-Emanuel sent Castiglione to speak with the Pope personally, on behalf of His Highness, she was successful in convincing the pontiff to not object to an Italian state. Castiglione was given a bracelet and tiara by the Pope, which she wore with pride.

L'accoudée (Leaning on the Elbow), 1856–57. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, albumen silver print from glass negative.

It must have been intoxicating to both the Countess and the Emperor to have her flex her ambassadorial muscles, and watch the most powerful figures in the world comply. She created a sensation which reverberated across the continent. When she debuted at the French Court, the Austrian Ambassador’s wife supposedly said [she was] “petrified before the miracle of her [Castiglione’s] beauty” and the Princess Metternich said “Wonderful hair, the waist of a nymph…in a word, Venus descended from Olympus…[but] after a few minutes she began to get on your nerves.”

La Dame de Cœurs (The Queen of Hearts), restaged between 1861-63. Photo by Pierre-Louis Pierson, albumen silver print from glass negative.

By February of 1856, Napoleon III and the Countess had begun an affair. The details of the affair, down to the exact date it began, are well documented. A masked Mardi Gras ball was given by Countess Le Hon on February 5, 1856. Apparently Paris society was scandalized by “escapades” between the Emperor and the Countess. Details were reported by the British Ambassador to France, Lord Crowley, in a letter he sent home to the Foreign Office. Soon the affair was a full-blown relationship. The following description is from a 1921 book titled “The True Story of Empress Eugenie” credited to de Savoie-Soissons, and purports to be a journal entry from an attendant at a party the couple attended together on February 17, 1857:

“Last night there was a fancy-dress ball at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Countess de Castiglione, who, they say, is on the most intimate terms with the emperor, had the most fantastic and daring costume imaginable. Half Louis XIV, half modern, it won her the title of Dame des coeurs, because of the numerous hearts embroidered on the gown...the Countess, she carried the weight of her beauty insolently. The proud Countess does not wear corsets; she would willingly be a model to a Phidias, if there were one, clad only in her beauty…. While [Horace de] Vieil-Castel Christians her Aspasia, [Charles Rohault de] Fleury calls her a female Narcissus, always in adoration before her own beauty, ambitious without grace and haughty without reason. Her reign was of a short duration; it lasted only about one year, during which time she resided at 53 rue Montaigne.”

Gown for the Comtesse di Castiglione, 1861-1867. From the collections at LACMA, (M.87.80.15).

The dress from this night is called the “Queen Of Hearts”, and in addition to Castiglione’s photographs of herself wearing it, taken to document the triumph of that evening, George Frederic Watts also painted her wearing the gown.

Castiglione’s husband, Verasis, filed for divorce midway through 1857. Records indicate their marriage did not end because of the affair. Verasis was enraged that his wife had spent something close to two million francs on clothing in less than two years, effectively bankrupting him. Teetering on the edge of financial ruin, being forced to beg the King for work - which was even more of an embarrassment since his wife’s infidelity was so public - Verasis left her and returned home to Sardinia with their son while the Countess stayed in Paris.

A year is not a terribly long time for a relationship to last, even as mistress to a married Emperor. History is filled with stories of women whose relationships with monarchs or other heads of government lasted decades, or their entire lives. The romance between Castiglione and the Emperor ended on April 26, 1857, when an assassination attempt was made on the Napoleon III as he was leaving the Countess’ apartment on Rue Montaigne.

Portrait in a White Dress, 1856–57, printed 1861–66. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, Salted paper print from glass negative with applied color, painter unknown.

Though not the first or last attempt made against his life, the Emperor listened to the whispers of his courtiers. They felt it was much too convenient the failed assassination had occurred as he was leaving Castiglione’s home, and the only way this could have happened was for the Countess to have been personally involved. The rumors were orchestrated by rivals of the Countess, perhaps even Empress Eugenie, in an effort to have her banished from court. It worked; Napoleon III broke off their relationship, Castiglione was no longer welcome at court, and she was effectively kicked out of Parisian society.

Countess Castiglione, September 1857, from page 11 of the Nigra Album (Disderi Studio carte de visite prints). By Pierre-Louis Pierson, albumen silver print from glass negative.

The Countess left Paris shortly thereafter, frustrated, as she’d had no involvement with the assasination attempt. She returned to Italy for a few years, but would return to Paris in 1861 to once again win over the bevy of European aristocrats who made the city their home. It became her second period of incredible social triumphs, documented by the hundreds of photographs she took with Pierson before she would begin her sad decline into madness and obscurity.

Fan belonging to the Countess Castiglione, 1858. Lace, mother-of-pearl, possibly Spanish in origin.

Since 2018 fashion historian Rachel Elspeth Gross has run her popular blog, Today’s Inspiration, about the history of high-end fashion design. Drawing more than 40,000 individual readers every day; Rachel’s ever-growing audience includes some of the biggest names in Fashion, Haute Couture, Fashion Journalism, and Fashion History academics. Her work has been featured in Women’s Wear Daily, the New York Times, Italian Harper’s Bazaar, and The National News; writes for The Vintage Woman magazine. A formally trained designer in her own right, in her spare time Rachel recreates 19th century ball gowns from scratch.

TEXT SOURCES:

Loliée, Frédéric (1912). The Romance of a Favourite. Paris-Club International du Livre.

De Montesquiou, Robert (1913). La Divine Comtesse: Étude d'après Mme la comtesse de Castiglione. Paris.

The Count de Soissons, Guy Jean de Savoie-Carignan (1921). The True Story of the Empress Eugénie. London: John Lane the Bodley Head; New York: John Lane Company MCMXXI. Pages 82-85.

Decaux, Alain (1953) La Castiglione, d’après sa correspondence et son journal inédits. Librairie académique Perrin.

Apraxine, Pierre, and Xavier Demange (2000).La Divine Comtesse: Photographs of the Countess de Castiglione. Exhibition catalog. New Haven: Yale University Press, in association with The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (Accessed August 5, 2022.)

Bowles, Hamish (August, 2000). Vain Glory. Vogue Magazine, pages 242-245, 270-271.

WEB SOURCES:

Boxeroct, Sarah (October 10, 2000). Photography Review; A Goddess of Self-Love Who Did Not Sit Quietly. The New York Times. (Accessed August 5, 2022.)

McPherson, Heather (2001) La Divine Comtesse: (Re)presenting the Anatomy of a Countess in The Modern Portrait in Nineteenth Century France. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. pages 38-75.

Daniel, Malcolm (July 2007). The Countess de Castiglione. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (Accessed August 5, 2022.)

Jana, Rosaline (January 4, 2017). The Scandalous, Narcissistic 19th-Century Countess Who Became Her Own Muse. VICE. (Accessed August 5, 2022.)

Stanska, Zuzanna (March 1, 2017). Virginia Oldoini, The Star Of Early Photography. Daily Art Magazine. (Accessed August 5, 2022.)