Virginia Oldoini, Countess of Castiglione, Part II

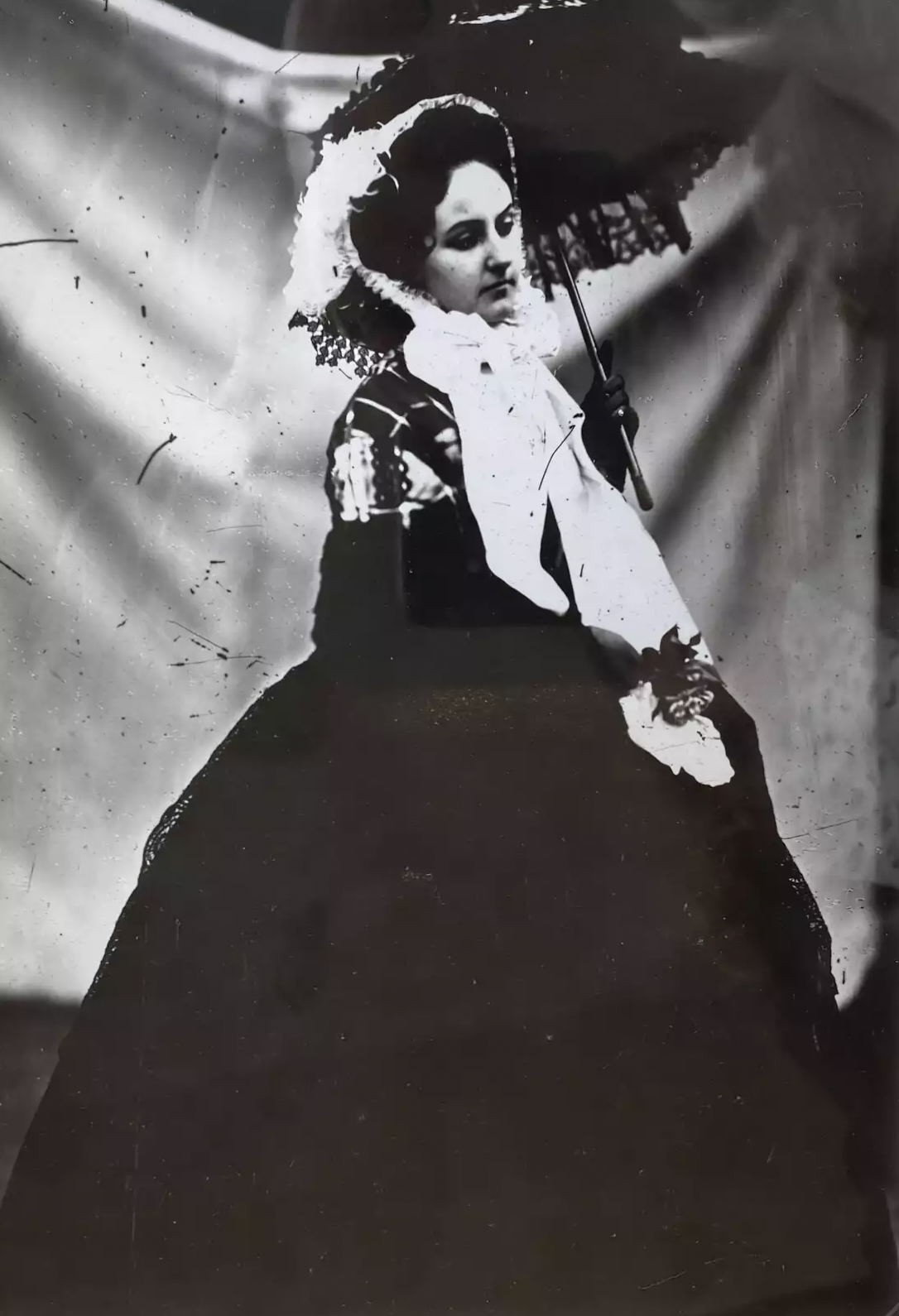

Chinese Woman and Marquise, 1861-1867. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, albumen silver print from glass negative.

In what became the introduction to their First Period (1856-1857) of work, Pierre-Louis Pierson photographed the Countess of Castiglione at his Mayer & Pierson studio in July of 1856. The photograph, titled “Portrait in a Black Dress,” is commonly assumed to be the first Pierson took of Castiglione. This one-time session would first evolve into a project, and then blossom into an association spanning many decades of creative achievement. At its end, a few years before Castiglione’s death, somewhere between 500 to 700 photographic images of the Countess had been taken.

Portrait in a Black Dress (1856) by Pierre-Louis Pierson. Salted paper print with ink retouching.

Barely nineteen, wealthy, beautiful and self-possessed, the photographs taken by Pierson during this First Period show how the instinctively captivating Countess connected with the camera from the first time one was pointed at her. When the pair started their collaboration, the Countess was nearing the end of her very brief marriage. This was a transformative period for Castiglione, and she had not yet actualized her creative voice. She also began working with Aquilin Schad, a painter who helped her to edit and color her photographs as the project progressed. The Countess unquestionably painted some of the images herself, though due to lack of attribution, it is now nearly impossible to know for certain who colored or embellished which image. In addition, the dates on the images are often vague or misleading; it is difficult to know the exact date (or often even a year) a specific image was taken.

An example of a painted version of one of Castiglione's portraits, circa 1860. Originally from a photo by Pierre-Louis Pierson, an albumen silver print from glass negative.

All told, 1856 was a bang-up year for the Countess of Castiglione. She had youth, beauty, access to staggering sums of money, and was wielding influence on a massive scale. None other than the Empress Eugenie was her romantic rival. Her extravagant costumes, and the occasional ridiculousness of her exploits, made her the subject of gossip in the finest parlors and publications across Europe. She scored an endless series of victories and didn’t hesitate to use her photography to catalog these triumphs.

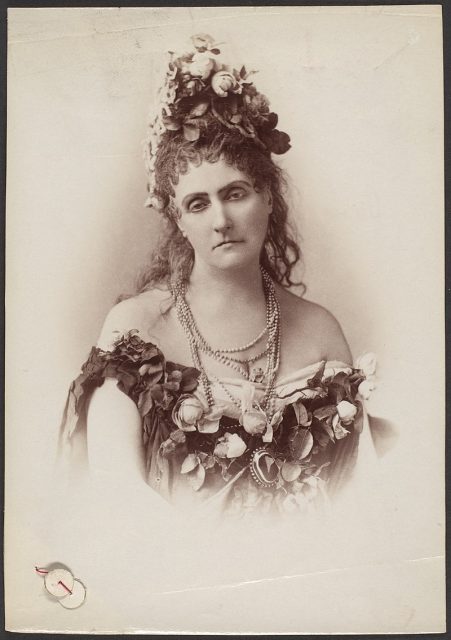

Castiglione as Béatrix, 1856–57, printed 1861–67. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, salted paper print from glass negative.

One such triumph was Castiglione’s entrance at a costume ball in early 1857 dressed as “the Queen of Hearts” on the arm of her lover, Napoleon III. Supposedly, the Empress approached her husband and rival to tell the Countess, "The heart is a bit low, Madame." Not only did the Countess have Pierson photograph the gown she wore during her triumph, she also had the prints painted so the image could be enjoyed in full color, work the Countess sometimes did herself. Using the picture as his reference, the painter George Fredrick Watts painted her in this costume in the early 1860s and further cemented the story in the annals of history.

La Dame de Cœurs (The Queen of Hearts), restaged in 1861–63. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, albumen silver print from glass negative.

But Castiglione’s reign was short-lived; later in 1857, when an assassination attempt was made on the Emperor and the Countess appeared complicit, her star fell as quickly as it rose. There is a theory this conspiracy was plotted by the Empress, who, knowing her husband’s wandering eye, decided she preferred a more compliant mistress in her spouse’s bed. Whatever the truth, Castiglione found she could not weather the scandal. She left Paris shortly thereafter, and returned to Italy

In 1861 the Countess returned once again to Paris, and settled in an area known as Passy. Thus began the Second Period (1861-1867) of her photographic work with Pierson. She used her relationship with the photographer to continue to document her social achievements as well as relive her earlier glories. This period would produce not only the largest number of images of any chapter in her life, but arguably her best. The most iconic images of her come from this period, and images taken in this period would forever change photographic portraiture.

Scherzo di Follia (The Joke of Madness), 1863-1866. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, albumen silver print from glass negative.

These Second Period images of the Countess are a combination of new and old victories and showcase her vision in its most complete form. Castiglione used photography as a tool for communicating with her world. These images were specifically staged to memorialize, publicize, and celebrate the events that mattered most to her. She would schedule a photoshoot after an event or party where she made a social impact, when she had a message she wished to convey, or (on occasion) a threat to make. She dressed herself for social events and for photo shoots in a range of controversial characters as diverse as Lady Macbeth, Ritrosetta, Madea, Anne Boleyn, Beatrix, the Madonna and the Bible’s Rachel. Afterwards, she would send the prints to friends, ex-lovers, and future conquests.

One Sunday, 1861–67. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, salted paper print from glass negative.

The Queen of Etruria, 1864. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, salted paper print painted in gouache.

For one series of images Pierson took of the Countess, she styled herself as the Queen Of Etruria, a mythological figure from the Iron Age. She intentionally depicted herself as an ancient warrior queen, knife in hand, ready to wage war. The point of the images was to stand up to her husband, who was not only divorcing her, but seeking to take away custody of their only child. Afterwards, Castiglione sent her spouse her portrait.

The Queen of Etruria, 1864. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, salted paper print painted in gouache.

For another series, the countess is dressed in a voluminous, muslin ball gown reminiscent of Marie Antoinette, who Castiglione also photographed herself as in caricature. The dress - basically a 19th century fantasy of an 18th century gown - was not historically accurate, but designed entirely for style over function. It was a version of a costume for a character from a Verdi opera worn by Elvira, a historic character who was said to be based on the adventures of Castiglione. If this is true, the photographs of Castiglione in this costume are self-referential and become an idealized version of herself quite literally celebrating her own fame.

Elvira at the Cheval Glass (Elvira at the Looking Glass), 1861-1867. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, salted paper print.

One of Castiglione’s more wicked stunts was attending a fundraising benefit party dressed as a nun, with a violinist following her about playing Chopin’s Sonata Op. 35 Mvt. 3, known as the Marche Funèbre (Funeral March). This was documented in a series of photographs called La Passe. The La Passe images were offered for charity, and are the singular example of Castiglione exchanging one of her photographs for money. The Countess gave her portraits away; at least part of the point was to invite her audience to stare at her, and she was completely at peace with her role as exhibitionist. She played to the advances of her voyeuristic admirers, and perhaps unsurprisingly, the Countess developed a reputation for narcissism and excess. Many of those she wished most to impress were often put off.

Sculptural Shoulders [Elvira variation] 1861-1867. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, salted paper print.

Castiglione led a life of intrigue. Despite the personal dramas she is remembered for and the many tales celebrating her eventual decline, during her life the Countess was connected with very powerful people and held incredible influence over the world she lived in. It is unclear how much of her influence was related to her minor titles, her personal appearance, or her diplomatic skills. Many details of her life were not documented or preserved (and what was preserved is not widely available) but documented tidbits of her political prowess do exist. One such example is a secret meeting she attended in 1871, just after the Prussian army had defeated the French. None other than Otto Von Bismarck summoned the Countess to speak with him about his siege of Paris. This was not an easy time for her - she had lost her ex-husband, her son, and the Emperor Napoleon III had been defeated - but in spite of her personal concerns, Castiglione was deft enough to talk the general out of immediately marching on Paris. She was somehow able to convince Bismarck to do so would be “fatal to his interests”, and Paris was delayed the tragedy of being occupied by Prussia.

The Hermit of Passy, sometime after 1863. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, albumen silver print from glass negative, retouched in charcoal and watercolor.

Reading anything written today about Virginia Oldoini might lead you to believe the Countess of Castiglione’s social supremacy and presence in the various courts and salons of Paris ended when Napoleon III fell. Yet at his defeat, she wasn’t even thirty. She was an incredibly beautiful, remarkably intelligent and educated woman deft in the art of conversation in many languages. She knew her life would go on - and it did. While she never had a lover with quite the same name recognition as Napoleon III, she never went without the attention of men, or friends when she decided she wanted them. There are records of Castiglione and rumors of her adventures through 1877.

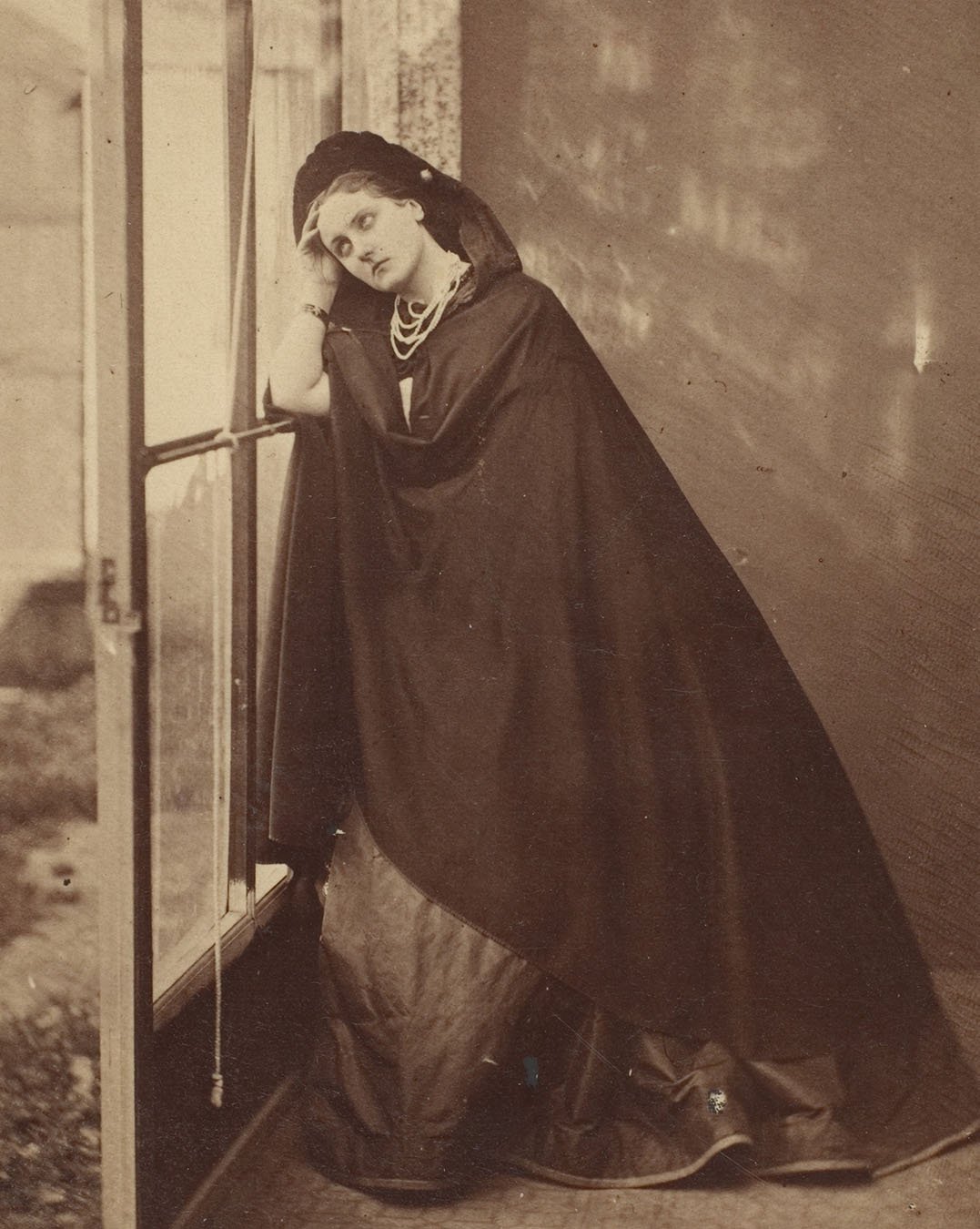

The Marquise Mathilde, 1861-1867. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, albumen silver print from glass negative.

It is true, however, that over the next decade, she began to decline. She behaved in increasingly eccentric ways, most of which sound like the onset of mental illness. The saddest part of her story is how she removed herself from the world. She spent the last fifteen to twenty years of her life in a self-imposed house arrest. She would not leave her home during daylight hours. When she did go out in public she would hide herself, specifically her face, behind gauzy veils, even though when she rarely did finally emerge, it was after dark. Thus she began a long hiatus of her photographic work with Pierson.

The Countess had a life-long relationship with mirrors. In her earlier photographic works she played with eye contact, creating the illusion she was looking at herself or the person viewing the photo. The indefinite intention of her various characters was part of the stories she told. Castiglione made it seem possible she could simultaneously do anything, and be anyone. Even when pretending to be ambiguous, her flashing eyes and confident body language belied any serious attempt at a display of innocence. Whether dressed as an ingénue or a nun, Castiglione was always herself in her photographs, with an expression that dared the viewer to stare back at her.

The Countess and Pierson began their Third Period of work together (1893-1895) very near the end of her life. The photographs which emerged from these sessions are arguably their most disturbing series, as they show a woman in her late 50’s and early 60’s falling apart. She leers at the lens, bizarrely comfortable and confident, especially since she had covered all the mirrors in her home out of fear of catching her own reflection.

Countess de Castiglione, 1895. From the Sèrie des roses. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, albumen silver print from glass negative.

As she declined in the last years of her life, the Countess tried to revive the excitement of her youth. Her decision to reunite with Pierson was to fulfill this fantasy for her end-of-life triumph, a final display to remind the world of all the marvels she had achieved. Yet, as she fell further and further into ill health (and possibly substance abuse), her photographic work became increasingly desperate. She squeezed her aging body into dresses she had worn and kept since her escapades as an ingénue. She made the same sort of coquettish expressions and tried to flirt with the camera as she had in decades prior. The results were at best strange, and often teetered towards the horrifying. These last images of her depict her as a woman changed, but one who cannot see the distorted image she is projecting.

Pensive,1893. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, albumen silver print from glass negative.

Most of the available information about the last few years of Castiglione’s life is morbid and sad, though, all things considered, she was very fortunate to have maintained relationships with the people in her life who mattered most. Pierson was one of these friends. There was to be an international exhibition in 1900, the Exposition Universelle, where Castiglione planned a retrospective of her work with Pierson, a celebration of their collaboration spanning decades. It would never happen.

Roses of Compiègne [Countess de Castiglione], 1895. From the Sèrie des roses. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, albumen silver print from glass negative

The Countess died on November 28, 1899. When it became clear large portions of her estate would not be released to her heirs, her remaining belongings were auctioned off, down to the bedroom furniture from the apartment she died in. Many of her personal belongings, including at least 433 original photographs, were purchased by Comte Robert de Montesquieu, a French poet, art collector and career dandy. The Comte wrote a biography of the Countess entitled La Divine Comtesse, which was published in 1913. His 433-piece collection eventually became part of the permanent collection of the Metropolitan Museum in New York City. In 2000 the Met held a retrospective of her photographic work. The catalog for this show contains a substantial portion of the images of the Countess, lent from various collections or selected from the museum’s sizable backlist.

Ti-fille brune [Countess de Castiglione], The Brunette Girl, 1895. From the Pitou Series. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, albumen silver print from glass negative.

The Countess was as infamous in death as in life. Scandalous newspaper articles delighted in labeling her a vain, arrogant narcissist. But it would be unfair to label her as any one thing. Had she been born a century later, there might not have been any limits on what she could have achieved. But consider what she did achieve. Despite the time and place in which she lived, she managed to find a life bigger than the wifely role she was raised to occupy. She made choices for herself in an era which discouraged women from doing so. She made an impact on the governance of Europe. And without a formal career, she created a body of work spanning most of the second half of the 19th century.

Roses of Compiègne [Countess de Castiglione], 1895. From the Sèrie des roses. By Pierre-Louis Pierson, albumen silver print from glass negative.

In the more than one hundred and twenty years since her death, the life and work of Virginia Oldoini, Countess of Castiglione, has been the subject of numerous articles, exhibitions, collections, and films. Her story has been adapted, her characters copied, and her clothing and personal items collected. In many ways, she achieved her goal of immortal and perpetual youth. She will always be an enigma, the shamelessly gorgeous young woman posing for the camera with a smile in her eyes for you, her lucky viewer. And perhaps…just perhaps…she would enjoy knowing her legacy has remained shrouded in mystery

Since 2018 fashion historian Rachel Elspeth Gross has run her popular blog, Today’s Inspiration, about the history of high-end fashion design. Drawing more than 40,000 individual readers every day; Rachel’s ever-growing audience includes some of the biggest names in Fashion, Haute Couture, Fashion Journalism, and Fashion History academics. Her work has been featured in Women’s Wear Daily, the New York Times, Italian Harper’s Bazaar, and The National News; writes for The Vintage Woman magazine. A formally trained designer in her own right, in her spare time Rachel recreates 19th century ball gowns from scratch.

TEXT SOURCES:

Loliée, Frédéric (1912). The Romance of a Favourite. Paris-Club International du Livre.

De Montesquiou, Robert (1913). La Divine Comtesse: Étude d'après Mme la comtesse de Castiglione. Paris.

The Count de Soissons, Guy Jean de Savoie-Carignan (1921). The True Story of the Empress Eugénie. London: John Lane the Bodley Head; New York: John Lane Company MCMXXI. Pages 82-85.

Decaux, Alain (1953) La Castiglione, d’après sa correspondence et son journal inédits. Librairie académique Perrin.

Apraxine, Pierre, and Xavier Demange (2000).La Divine Comtesse: Photographs of the Countess de Castiglione. Exhibition catalog. New Haven: Yale University Press, in association with The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (Accessed August 5, 2022.)

Bowles, Hamish (August, 2000). Vain Glory. Vogue Magazine, pages 242-245, 270-271.

McPherson, Heather (2001) La Divine Comtesse: (Re)presenting the Anatomy of a Countess in The Modern Portrait in Nineteenth Century France. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. pages 38-75.

WEB SOURCES:

The Met (May 8, 2000) "LA DIVINE COMTESSE," PHOTOGRAPHS OF THE COUNTESS DE CASTIGLIONE, Press Release. (Accessed August 30, 2022)

Boxeroct, Sarah (October 10, 2000). Photography Review; A Goddess of Self-Love Who Did Not Sit Quietly. The New York Times. (Accessed August 5, 2022.)

Daniel, Malcolm (July 2007). The Countess de Castiglione. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (Accessed August 5, 2022.)

Galindo, Brian (September 9, 2013). 25 Stunning Photographs Of Countess De Castiglione. Buzzfeed. (Accessed August 5, 2022.)

Jana, Rosaline (January 4, 2017). The Scandalous, Narcissistic 19th-Century Countess Who Became Her Own Muse. VICE. (Accessed August 5, 2022.)

Stanska, Zuzanna (March 1, 2017). Virginia Oldoini, The Star Of Early Photography. Daily Art Magazine. (Accessed August 5, 2022.)