Arbiters of Style: Sportswear History

Advertisement for Redfern's newest collection, from the New York Tribune, circa 1885.

Before John Redfern began offering tailored women’s clothing, the concept was inert- the idea of tailoring was based on utility and not considered to be decorative or high-end.

At the turn of the 20th century, women’s lives were changing, and this style of dress would become a staple for the middle class American woman.

By the end of the fiscal year in 1931, sportswear was a multi-billion dollar market.

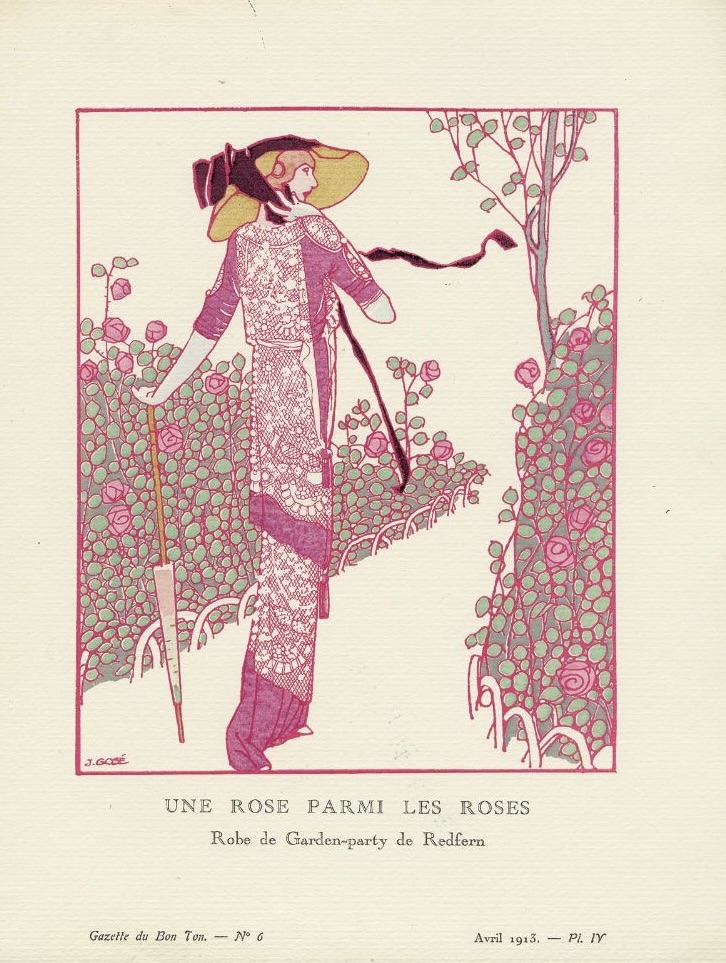

Une Rose Parmi Les Roses,Robe de Garden-party de Redfern / A Rose Among Roses, Garden Party Dress by Redfern. April 1913.

Sportswear, at least in the context of women’s ready-to-wear, basically means coordinated separates, which have been designed to mix and match.

In America, prior to increasing worker freedoms from the mid-late 19th century onwards, leisure had been a luxury available only to the leisured classes during the Industrial Revolution (c.1760-1860), and before that, Puritan America had condemned leisure for all.

Redfern Newspaper Advertisment; Autumn 1887.

American sportswear would become a “global phenomenon," but the origins of it start in Europe. At first, American designers essentially (mostly) copied French designs, reinterpreted them for the US market.

Before it became the American Look, it described apparel that we call ‘activewear’ today, designs intended to be worn for sports, and other, similar activities. As the 19th century progressed, women began to participate in more outdoor activities. Bicycle riding, swimming (bathing), and tennis were not possible with long skirts, women needed clothing that allowed for more mobility.

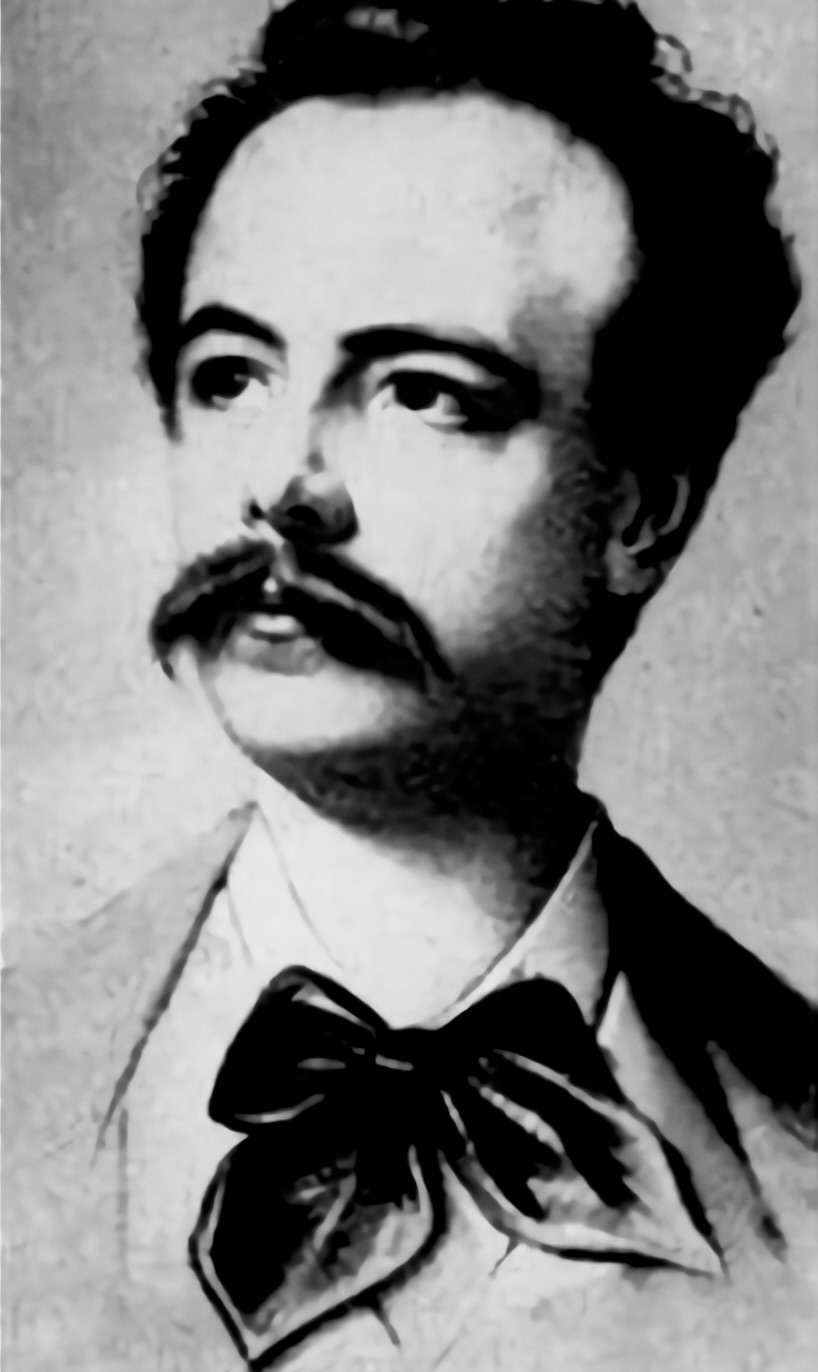

John Redfern. Date and Photographer Unknown.

It could be argued that Redfern, or later, Redfern & Sons, was really the first house (at least in Europe) to offer sportswear for women.

Before Redfern, there were no sporty, jaunty options for ladies of leisure to wear while yachting, riding, or perambulating, as ladies of the late 19th century were known to do.

By the 1880’s the house was patronized by aristocrats from across Europe, though the American branch never took off with the same velocity. In 1889 the house was named Dressmaker By Royal Appointment to Her Majesty the Queen (of England). The house also produced formal wear and ‘Specialty’ undergarments; aka, Redfern's proprietary corset.

John Redfern, for Redfern Couture, jacket, circa 1892, made of silk with glass beads. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. The Schofield Collection.

Redfern, who was born in 1820, was the son of a tailor. With the help of his sons, he opened a “Ladies Tailoring” house in London, a couture branch in Paris, and a combination imports-and-fur shop in New York City. At one point the house employed more than 80 seamstresses and tailors who lived and worked at the firm. For reasons lost to time, apparently these ladies were referred to as the “Bunny Girls”.

Sales salon at Redfern fashion house, Paris. Photograph by Charles Eggiman for Les Createurs de la Mode (1910).

After designing the bridal party’s gowns for Eliza Hoffmeister (daughter of a wealthy doctor) in 1869, Redfern began to attract more attention from the fabulously wealthy families, which would support his brand well into the next century. These clients included Princess Alexandria of Denmark and Queen Emma of the Netherlands. In 1879 Redfern designed a traveling dress called the 'Jersey Lily,' named after Lillie Langtry, the actress who had commissioned the design.

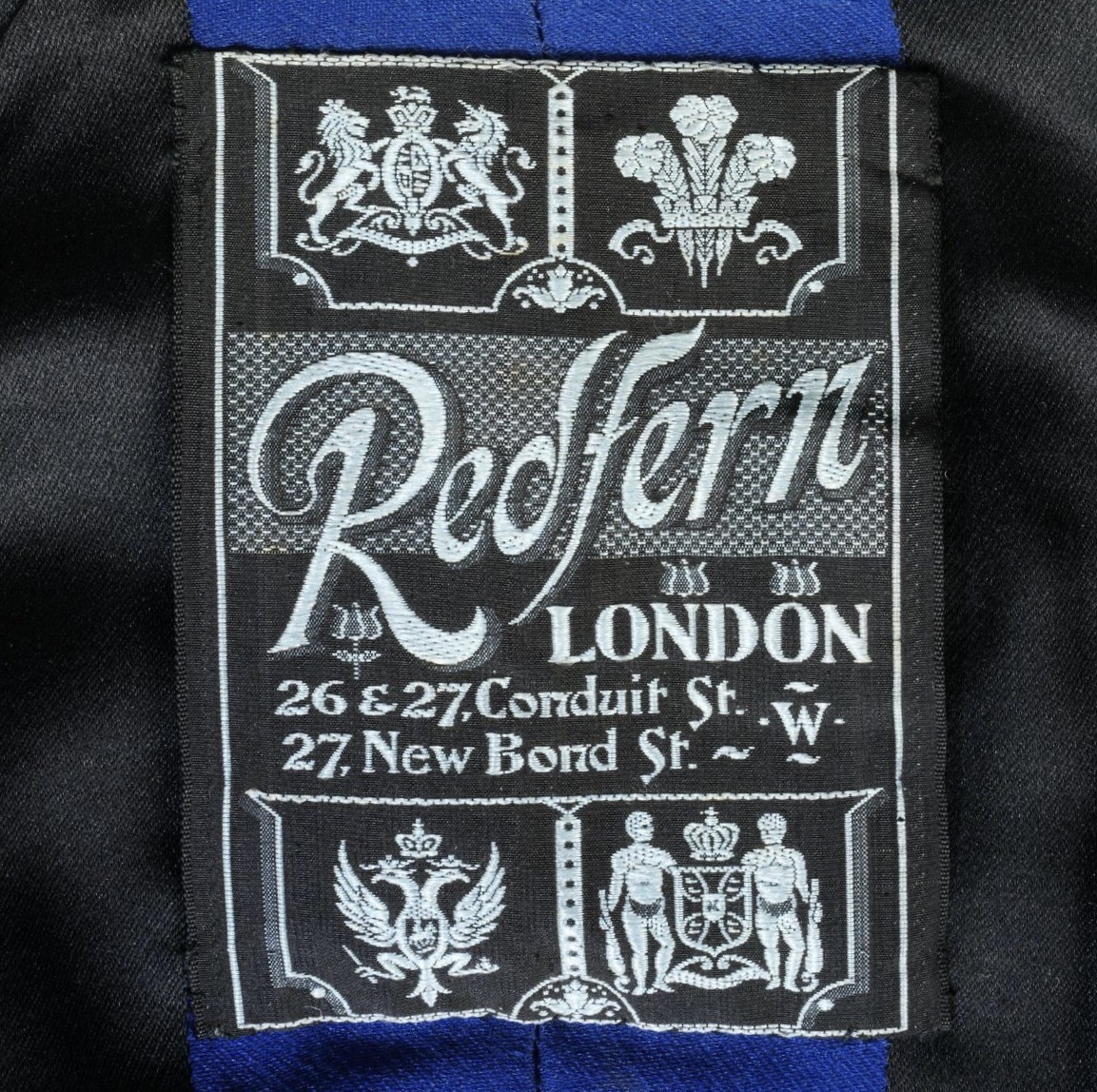

Label from a Redfern Walking Costume, circa 1909.

In 1916, after the death of John, under the direction of his sons, Redfern designed the first, official women’s uniform for the Red Cross. The brand floundered after the death of its creator, and locations closed and reopened until 1940, when it finally closed for good.

By the late 19th century it was becoming increasingly common for modified menswear to be used in activewear and was also an essential part of a working woman’s wardrobe, like the shirtwaist comes from a man’s shirt. A man could indicate he was in a casual, leisurely situation by removing his coat. A woman could do the same by wearing a shirtwaist and skirt instead of a dress.

Photo of Coco Chanel during a working visit to Los Angeles, in 1931, originally published in the LA Times. Digital colorization by Lee Ruelle.

Coco Chanel was another early designer of sportswear, she didn’t design sportswear as much as she designed couture for the "sports type." Chanel’s designs were haute couture, even if sporty, and the garments she designed were for the wealthiest of ladies. Chanel never designed for the everyday woman.

Metro Goldwyn Mayer even had her on a million dollar retainer, and would fly her to Los Angeles twice a year just to design gowns for their stars. Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich were her private clients.

Gabrielle Bonheur "Coco" Chanel, born in 1883, is still an icon of fashion almost 50 years after her death. She was one of the designers credited with liberating women from the corseted silhouettes that were still commonly in use in the early 19th Century. She introduced the high fashion world to Jersey Fabric, both contributions that would be integral to the American version of the upper-class European style.

Samuel Goldwyn and Chanel in L.A. circa 1931. From the Samuel Goldwyn Jr. Family Trust and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

She created the now classic, feminine lines of a woman’s formal suit, and in 1915 Harper’s Bazaar, according to Sleeping with the Enemy: Coco Chanel, Nazi Agent by Hal Vaughan, would say "The woman who hasn't at least one Chanel is hopelessly out of fashion.” Though her designs changed the trajectory of womens wear, Chanel was and is a controversial figure, especially due to her choices during the Second World War. Coco convinced the world (or at least let people believe) that she had invented “Little Black Dress,” though there’s plenty of proof that other designers made them earlier. As an example Ara Frenkian, an Armenian designer and tailor who worked in Paris at the same time, said that “it was Jenny [Sacerdote] who first invented the little black dress, not Chanel.”

Gloria Swanson in a Chanel-designed gown in 1931’s Tonight or Never. Digital colorization by Lee Ruelle.

Though haute couture designers like Chanel offered pieces that could be considered sportswear, it was rarely the focus of design. There were a couple of exceptions to this, like Madame Balouzet Tillard de Tigny (real name Jane Régny) who designed couture for playing sports and outdoor travel. Or Suzanne Lenglen, who was the sportswear department director at the house of Jean Patou. Both these ladies had been famous tennis players. The clothing they created was made to measure, and designed for specific physical activities. Its European inception was vital, made sportswear more and more commonly accepted for everyday use, and the big names of the Paris designers who created it in the late 19th and early 20th centuries brought press attention, and what a modern woman wanted to wear began to change.

Back view of fashion models in swimsuits; Toni Frissel for Harper's Bazaar, January 1950.

In Part Two, we will contrast American Sportswear against it's Euopean predecessor, and follow this history of sportswear as it makes its transition, stateside, into what we today think of as The American Look.

Since 2018 fashion historian Rachel Elspeth Gross has run her popular blog, Today’s Inspiration, about the history of high-end fashion design. Drawing more than 40,000 individual readers every day; Rachel’s ever-growing audience includes some of the biggest names in Fashion, Haute Couture, Fashion Journalism, and Fashion History academics. Her work has been featured in Women’s Wear Daily, the New York Times, Italian Harper’s Bazaar, and The National News; writes for The Vintage Woman magazine.

A formally trained designer in her own right, in her spare time Rachel recreates 19th century ball gowns from scratch.

SOURCES:

Mackay-Smith, Alexander, et al. (1984) Man and the Horse. The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Simon and Schuster, New York.

Milbank, Caroline Rennolds. New York Fashion: The Evolution of American Style. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996.

Callan, Georgina (1998) The Thames and Hudson dictionary of fashion and fashion designers. Thames and Hudson, New York.

Vaughan, Hal (August, 2011) Sleeping with the Enemy: Coco Chanel, Nazi Agent. Chatto & Windus.

Lockwood, Lisa (September 8, 2012) Sportswear: An American Invention.Women's Wear Daily.

John Redfern, Tailor; 1820-1895. (September 19, 2015) Blue 17 Vintage Clothing Blog.

Kenworthy, David (November, 2015) How sportswear became high fashion. Origin Outside.

Kashner, Sam (February 8, 2017) Coco Chanel’s Little-Known Flirtation with Golden-Age Hollywood. Vanity Fair.

Hidden, Concierge (November 9, 2018) Should we raise the dead of fashion? Vanity Fair France.

Redfern Couture Jacket (1892.) By John Redfern. The Schofield Collection, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne. Purchased with the assistance of a special grant from the Government of Victoria, 1974.

Woman model, standing in an office, smoking while modeling undergarments, 1949. Photographed by Stanley Kubrick (yes, the same Stanley Kubrick you’re thinking of.) Look magazine photograph collection, at the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.