More Than A Muse; Henriette Negrin, the Inventor Behind Fortuny

Henriette Negrin at work in the Palazzo Pesaro Orfei, photograph by Mariano Fortuny, circa 1909.

Anyone who is interested in the history of apparel has at least heard the name Fortuny. Marcel Proust, generally accepted as be one of the most influential authors of the 20th century, wrote about the haute couture house more than once in his seven volume novel, probably best known in the U.S. as Remembrance of Things Past (1913 -1927).

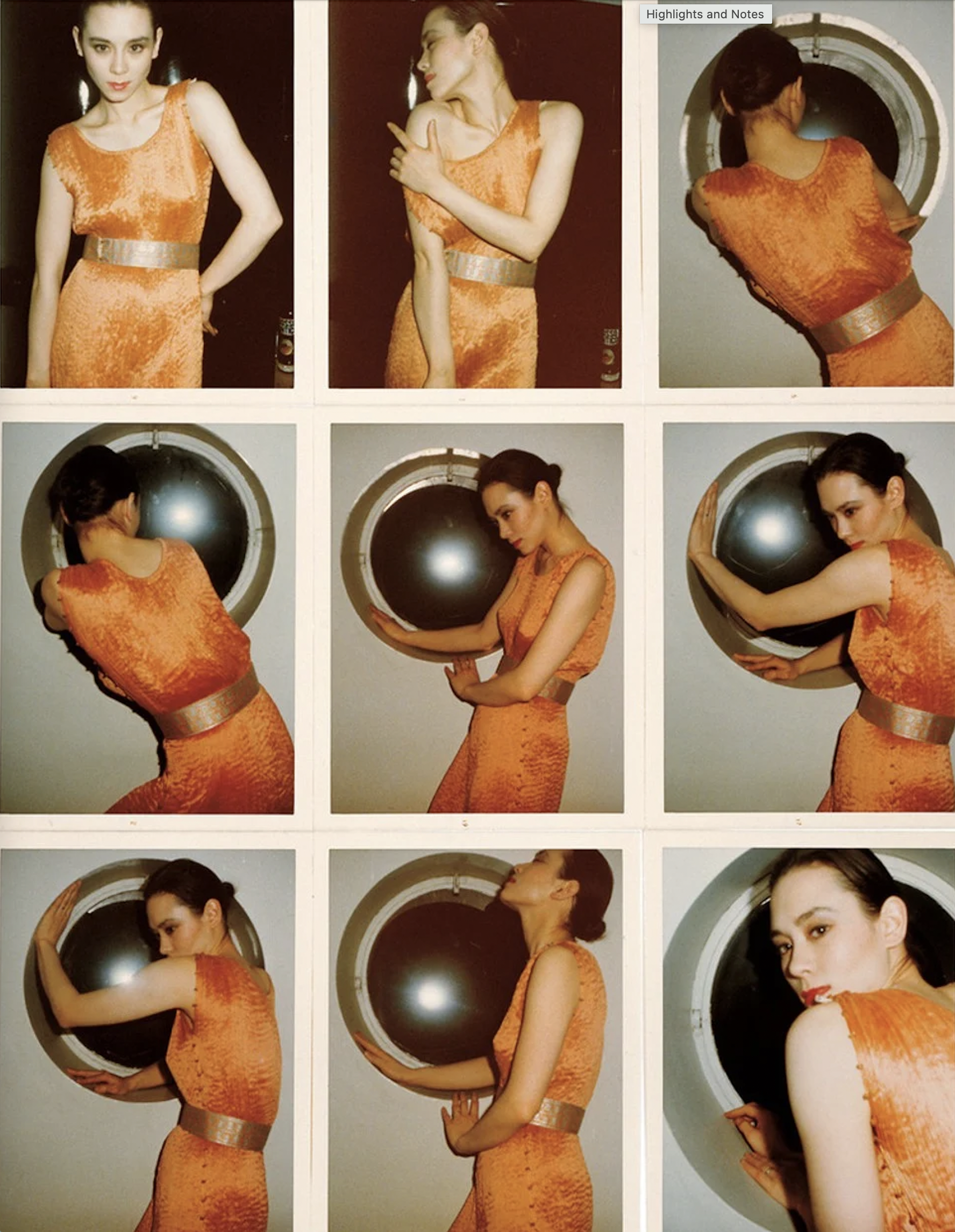

Decades later, in the 1970s, supermodel Tina Chow began to collect Fortuny pieces. Both to restore them, and to wear to very public places and events. Her talent, and the callaboritive work Chow created in the interest of protecting Fortuny's memory, brought the name back to magazines and newspapers. It was more than sixty years after the house first began to produce gowns influenced by ancient Greece, finely pleated in a manner that has never been successfully duplicated exactly.

Tina Chow posing in a Fortuny gown for Antonio Lopez circa 1975.

The Delphos gown was the first, and it was patent protected, which means it was officially registered with the Office National de la Propriété Industrielle in 1909. The language is very specific:

“The dress consists of a robe, open both at the top and at the bottom, whose width can be equal to its length, widening or narrowing from top to bottom or at various points, in accordance with the general appearance and aspect one desires to give to the dress. The fabric can be smooth or pleated; this detail is an independent invention.

The upper section is laid flat so that the two edges are level and these are then fastened at points d and e in whatever way one decides; an opening in the center forms the neckline, two lateral openings are for arms through with, in between, two openings whose edges are laced together. Between the lateral points e and g strings are attached obliquely to adjust and modify distance x which determines the bottom of the sleeve in accordance with the size and height of whoever is wearing the dress. These strings are on the inside of the dress so as to be invisible.”

Henriette Negrin wearing a prototype of the Delphos Gown, photograph by Mariano Fortuny, circa 1907-1909.

The language is difficult on purpose. Part of the way that trade secrets in apparel design are kept private is to patent specific components that legally protect your creation while masking your process, especially when you have invented a machine. This is an important factor to consider if a person wants to make an objective assessment about the over-simplification that obscures the true history of the House of Fortuny and its fabulous creations. That story matters for many reasons, only one of which is that the work the house produced continues to rouse the interests of the fashion community more than 110 years after its debut.

"Mariano on the Terrace," photograph by Henriette Negrin, circa 1910.

In the commonly accepted story about these legendary pleated masterpieces, Mariano Fortuny is a genius whose solitary vision was part of the social movement that allowed women to first shed their restrictive corsets. Though a lovely story, it is essentially a fairy tale, and when it is told, Fortuny’s partner and eventual wife, Henriette Negrin, is typecast as the selfless Muse, existing solely in a passive, supporting role.

That is more than inaccurate, and it does the memory of Fortuny no better than it does his wife. Henriette Negrin has always been more than inspiration. Specifically, and long before she met the man who would become her husband, she researched pigments for dyeing fabrics, learned to apply the dyes herself to stencils she learned to make for printing textiles. She built her own career and reputation. It was a good one.

Elena vestida con túnica amarilla (Portrait of Elena Sorolla García wearing a yellow pleated silk Delphos gown by Mariano Fortuny), painting by Joaquín Sorolla, circa 1909.

The legend of Fortuny, sadly, is a narrative which excludes the actual inventor of the machine which pleated the gowns in such a manner that has never been exactly reproduced. In the same patent documents quoted above, there is a handwritten note from Fortuny. This is what it says:

“This patent is owned by Mrs. Henriette Brassart who is the inventor. I enclosed this patent on my name/behalf due to the urgency of the deposit…in Paris June 10, 1909.”

"Henriette in Kimono," photograph by Mariano Fortuny, circa 1915.

Brassart was Negrin’s mother’s maiden name, and we must remember that when these documents were submitted, the rights held by men were not necessarily guaranteed to women, and in many cases women were simply unable to participate, officially or otherwise, in the circles of legitimate business which would allow one to protect their innovations and inventions.

Lisa, Anna and Margot Duncan, adoptive daughters of Isadora Duncan, wearing Delphos dresses by the House of Fortuny. Photograph by Albert Harlingue, circa 1920, © Albert Harlingue/Roger-Viollet, Paris, France, HRL-512376.

Long before she met Fortuny, Negrin was already an established apparel and textile designer, and if you look into the research about her life, she seems to have been a bit of a self-trained engineer. Sometime around the turn of the 20th century, the couple met in Venice, where Negrin was living and Fortuny had come to visit friends. We know for certain that Negrin moved to Paris in 1902, where the Catalan/Spanish autodidact Fortuny lived. His father had died when Mariano was a baby, and his mother took her children to Paris to be closer to her own family. The couple was together for almost 22 years before they married in February of 1924. All told, Fortuny and Negrin spent 47 years together as partners.

Margaret Morris posing in “The Dance of the Bow,” photographer uncertain, circa 1936.

To be very clear, the House of Fortuny was not a husband exploiting his wife’s abilities, there are many examples (like in the patent language above) where Fortuny went out of his way to be sure that on the formal documentation, the papers that really mattered, Negrin was given full credit. Theirs was a fully realized creative team; they worked together in concert.

Painting of Henriette Negrin by Mariano Fortuny, circa 1915.

Fortuny had a reputation for being able to hand pleat better than any other designer. Negrin was a woman who knew textiles in an intimate way, in a manner that it may not have been possible for a man in that era. At least not without great exception. If that sounds off to you, consider this; who was responsible for laundry? It makes complete sense that these two were drawn together, and stayed together, until Fortuny’s death in 1949. She “originated a number of the Fortuny fabric’s colorways,” which were the product of her own research, and often it was her hands plunging those fabrics into her dyes, figuring out how to achieve a specific shade or tone.

Signature on the interior French seam of a Fortuny gown, date and photographer unknown; © Fortuny Museum/FCMV.

When Mariano died, on May 3, 1949, the House of Fortuny stopped producing Delphos gowns. That fact has contributed greatly to the mythology and misattribution of the couple’s joint work, and the individual contributions of Henriette Negrin. It was not Mariano Fortuny who created the story, but our culture after his death.

The Palazzo Pesaro Orfei, Venice, circa 1985; © Fortuny Museum/FCMV.

If you look at the contemporaneous documentation, the objective, first-person source material, the story is crystal clear, and it effected The House of Fortuny’s business practices. They were groundbreaking for many reasons, one of them was the manner in which they handled international distribution, refusing to have multiple dealers in the same country, or to license their designs, which would essentially reveal the trade secrets behind how they achieved their miraculous pleats.

Mariano Fortuny Painting, photographer unknown (possibly Henriette Negrin) circa 1930; © Contrasto.

As to when the Delphos gown debuted, sources differ, it’s sometime either just before their patents were registered, or around 1907; there are Fortuny photographs of Negrin wearing a prototype. The mystery was important. Negrin sent a letter to the exclusive distributor of Fortuny fabrics in America, Elsie McNeill Lee that the designs for the Delphos gowns were her own.

Two Evening Dresses by the House of Fortuny, circa 1920s, Gift of Gloria Barggiotti Etting (1980), to the Metropolitan Museum. Accession Number: 1980.170.

After Fortuny’s death in 1949, she sent another letter to McNeill Lee, regarding her decision to stop production:

“…Regarding Delphos, after mature consideration – and this is why I have been slow to answer – I have irrevocably decided to cease all commercial production. Similarly, given that these garments are of my own creation, even more than any other, I desire that no-one [sic] else take them over, and thus to the sale of the Delphos we must apply the words 'the end.'”

The House of Fortuny photograph which shows the correct way to store a pleated gown. This image is from the house’s first new recreated collection from Paris Fashion Week Fall 2017. © Fortuny Museum/FCMV.

Negrin lived until 1965. She spent the last 16 years of her life indexing and organizing the Fortuny archives, as well as Mariano’s personal collection of fine art. In addition to his work in apparel design, he had been an accomplished painter and photographer. When she died, in Venice, Negrin bequeathed the Fortuny Palace to the city, which turned it into the Palazzo Fortuny museum.

Today, the brand still produces and sells luxury fabrics.

Since 2018 fashion historian Rachel Elspeth Gross has run her popular blog, Today’s Inspiration, about the history of high-end fashion design. Drawing more than 40,000 individual readers every day; Rachel’s ever-growing audience includes some of the biggest names in Fashion, Haute Couture, Fashion Journalism, and Fashion History academics. Her work has been featured in Women’s Wear Daily, the New York Times, Italian Harper’s Bazaar, and The National News; writes for The Vintage Woman magazine.

A formally trained designer in her own right, in her spare time Rachel recreates 19th century ball gowns from scratch.

WEB SOURCES:

Lambert, Bruce (January 26, 1992.) Bettina L. Chow, Model and Designer, Dies at 41. The New York Times. (Accessed July 5, 2022.)

Smith, Wendy L. (2014) Reviving Fortuny’s Phantasmagorias; a Thesis. University of Manchester, School of Arts, Languages and Culture.

Byatt, A.S. (June 24, 2016.) Lives Entwined: the genius of William Morris and Mariano Fortuny. The Financial Times. (Accessed July 5, 2022.)

Simmonds, Janet (2019.)Venice – Fashion, Fortuny, Silk dresses and Downton Abbey. The Educated Traveler. (Accessed July 5, 2022.)

Álvarez, Alba Sanz (2021) Mariano and Henriette Fortuny: Notes on Co-Creating the Delphos Gown. The Fashion Studies Journal. (Accessed July 5, 2022.)

Fortuny.com (February, 2021)Be The Muse: Henriette Negrin. (Accessed July 5, 2022.)

No Author Listed (June 18, 2021)Textile Talks: Fortuny and the Timeless Tides of Design. Four Hotels & Travel.

Parker, Allison (April 6, 2022.) Inner Threads of a Fairytale; Fayetteville’s Elsie McNeill Lee becomes Venice’s Countess Gozzi and President of Fortuny. East Coast Lux Magazine. (Accessed July 5, 2022.)

David Seidner Archive (multiple dates) The International Center for Photography. (Accessed July 5, 2022.)

History Page (undated) Fortuny.com (Accessed July 5, 2022.)

BOOKS & PRINTED SOURCES

de Osma, Guillermo (2015) Mariano Fortuny; His life and work. V&A Publishing, London.

Bañares, Silvia (2017) A Short Biographical Note on Henriette Nigrin, Creator of Delphos. Datatèxtil 36 (pages 73–84.)

Brevet D’Invention, genre d’étoffe plissée-ondulée, Office National de la Propiété Industrielle. (June 1909) M.8.1.5, Il Fondo Mariutti Fortuny, Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venice. (Patent of Invention, pleated fabric, National Office of Industrial Property, June 10, 1909, M.8.1.5, Mariutti Fortuny Collection, Marciana National Library, Venice.)

Proust, Marcel (a seven volume novel published between 1913–1927) À la recherche du temps perdu (French); In Search of Lost Time or Remembrance of Things Past [depending on whose translation and what year it was publised]. This is a very interesting article about the divisions between the devotees to one English language translation/title over the other.

"Study for the Pink Dress," painting of Henriette Negrin by Mariano Fortuny, circa 1932.

Do you have expertise or information about the House of Fortuny that we NEED to know? Or are you a vintage seller or collector who'd like to talk about fortuny? We would love to chat. Our contact page can be found here.

We want to be certain that we are providing information that helps this community we love so much. And we want YOU to be part of that conversation. Our contact page can be found here.